From Jacobin

Nativist Reapportionment Theory Redux

By the late 1970s, only a decade after the legislative reapportionment revolution, nativist organizations began developing a renewed theory of apportionment. Organizations like the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR) and its legal arm, the Immigration Reform Law Institute (IRLI), argued that the “one person, one vote” standard articulated in the Supreme Court’s Wesberry v. Sanders decision required excluding “illegal aliens” from population figures used in congressional and state-level redistricting.

Despite repeated dismissals of apportionment cases, FAIR’s nativist arguments continued to percolate through the courts between the 1980s and 2000s. FAIR-style claims re-emerged most prominently in Evenwel v. Abbott (2016), where two Texans contended that including undocumented immigrants in state redistricting counts violated the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause because it “diluted” the power of their votes.

The nativist argument is at the heart of the Trump administration’s efforts to exclude undocumented immigrants from congressional apportionment counts for the first time in American history.

The Supreme Court unanimously agreed that it was constitutional for Texas to use total population figures in redistricting, but left the constitutionality of nativist reapportionment schemes unresolved. Justice Clarence Thomas went even further, announcing in a concurring opinion that there is no constitutional basis for the “one-person, one-vote” principle.

The table of contents in IRLI’s amicus brief in Trump v. New York spells it out in two blunt sentences:

A. “Only Members Of Our National Political Community Should Be Represented In Our National Government.”

B. “Illegal Aliens Are Not Members Of Our National Political Community.”

Supplementing the nativist logic is an emboldened theory of the imperial executive branch, which holds that the president may, via memo, evade statutory and constitutional requirements that apportionment be based on the tabulation of “total population” of each state.

While neither the administration nor its supporters can cite a single historical example to support their argument that the president can fix House apportionment on a whim, the ghost of Evenwel haunts the briefs. And at any rate, a court stacked with Trump appointees will likely be more open to alternative theories of reapportionment than the one that decided Evenwel.

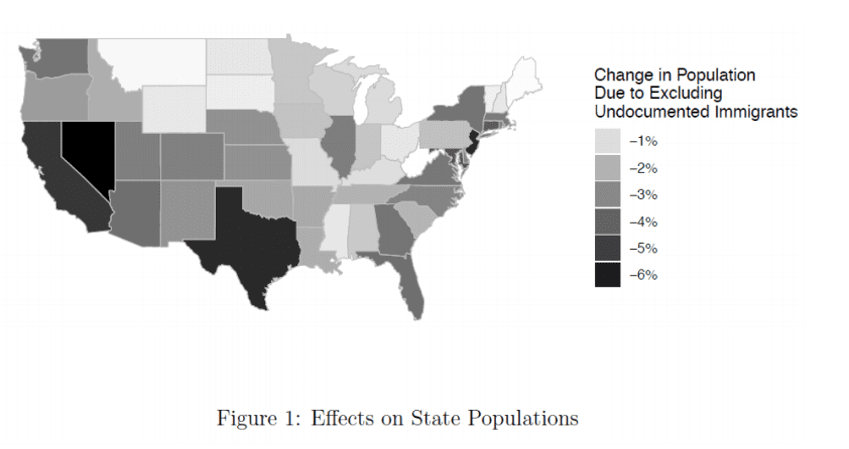

The material effects of making undocumented immigrants vanish in the congressional count are hard to overstate. States with larger populations of undocumented immigrants would lose as much as 6 percent of their apportionment populations, while more homogenous states like Montana, West Virginia, and Maine would be safe. Texas would lose a congressional seat. California and New Jersey might too, and Arizona, Florida, New York, and Illinois would also be in danger.

Those losses would be mirrored in the Electoral College, further biasing presidential contests. And a fall-off in representation would mean a corresponding decline in federal dollars. Typically, an extra congressional seat translates to as much as $100 per capita in additional federal funding. As George Washington University researcher Andrew Reamer notes, because apportionment numbers are used as official tabulations in statutory formulas, the effects on funding could be far more dramatic:

Equally disturbing is what it would mean to open the door to the idea that Congress (or state legislatures) can redistrict on the basis of a principle other than total population. If undocumented immigrants can be excluded, there would be little stopping right-wing legal theorists from articulating other redistricting criteria. The result would make current partisan gerrymanders in states like Wisconsin look quaint by comparison.

The future of the 2020 apportionment controversy is not clear. While the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on the case later this month, the Census Bureau has indicated that it may not be able to comply with the Trump memorandum by the apportionment deadline of December 31.

Even if Trump does send “his” numbers to Congress, the House of Representatives could still refuse to accept them, which would likely set off a chain reaction of litigation that could take some time to resolve.

But whatever the outcome, this episode reveals that Trump’s refusal to concede the election, however audacious, is consistent with a far more potent, and more powerful, strand of counter-majoritarianism with deep historical roots in the Republican Party. It is a strategy whose success derives in part from being unspectacular, buried in briefs, barely perceptible even to seasoned political observers.

And it is the kind of ideology that cannot be fought with defensive legal argumentation alone. It requires a good offense: a vision for reconstructing American political institutions that gives the majority — the most important number in a democracy — a voice.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.