From Jacobin

Talking Union

Founded in 1893, the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) had cut its teeth on a series of hard-fought battles for union recognition in the mining ranges of Colorado, Montana, and Utah. These fights were part of a broader intensification of class struggle across the United States, which no doubt also influenced workers in the Copper Country, where the Finnish Socialist Federation and other left-wing organizations were significant players in working-class life. Though the mines were still union-free, workers in other Copper Country industries were increasingly launching organizing drives — and winning.

Buoyed by its success in the West and confident that the miners of Copper Country would be drawn to the prospect of a unified, coordinated strike, WFM organizers began preparing the ground in 1912. They identified four key grievances: low wages, unsafe working conditions, the introduction of a new one-man drill that risked miners’ lives and eliminated jobs, and — most importantly — the employers’ refusal to recognize the union.

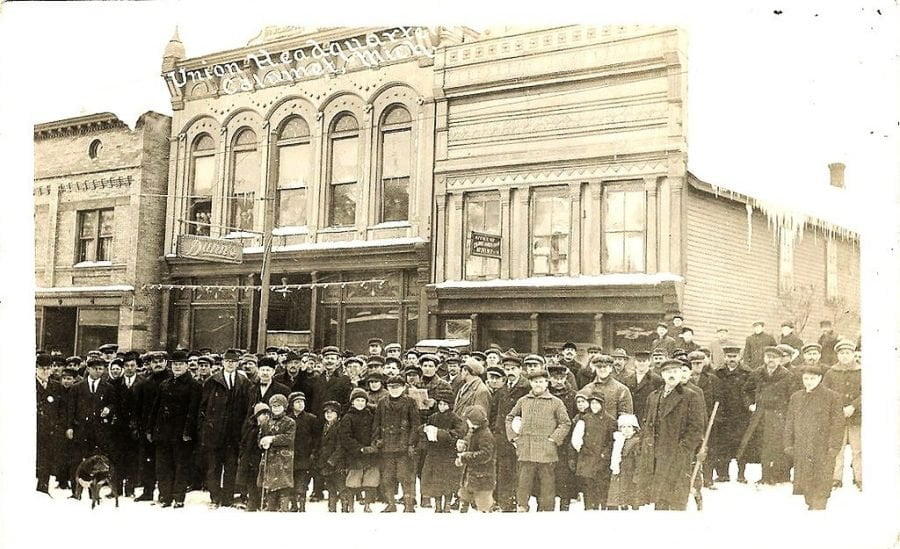

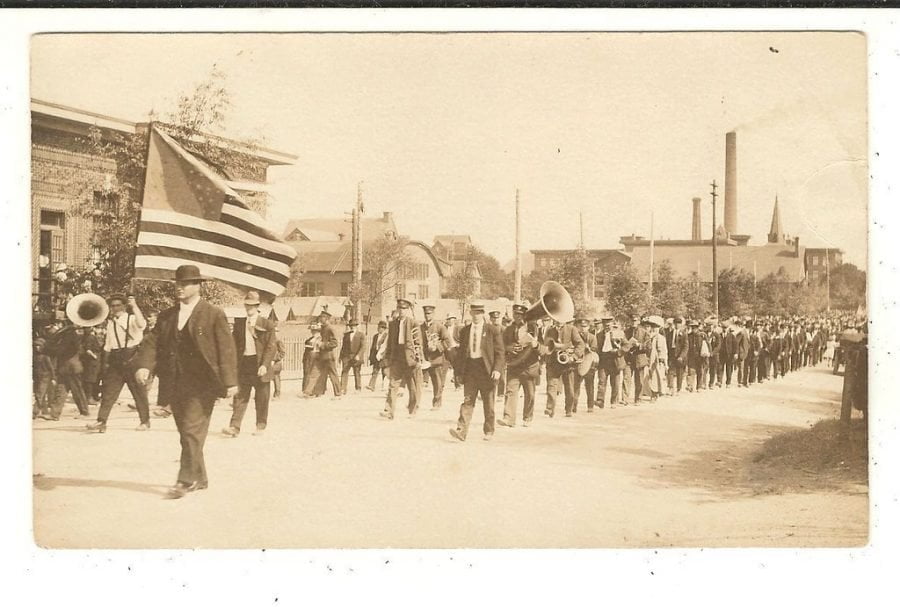

Labor parades and rallies took place throughout the spring of 1913. Työmies reported on a rally of three thousand “wage slaves” from the Calumet and Hecla mines on June 10. Only two days prior, thousands of workers had marched through downtown in a mass rally organized by the Calumet Miners’ Union.

Charles Lawton, general manager of the nearby Quincy Mine, wrote on June 18 that “Many of our best men have joined the Western Federation, and at times are brought into joining with and listening to the socialists.” Two weeks later, things had grown critical: “I am again very much concerned over the present labor situation.… The temper of the Finnish employees today is unprecedented in all of my experience, and is almost unbearable.” His colleague MacNaughton is alleged to have sworn that “grass will grow in the streets before C&H recognizes the union.”

Later that month the WFM submitted its final ultimatum: recognize the union and open negotiations over its demands, or face an indefinite labor stoppage. Lawton allegedly returned his letter unopened, and on July 23 the Western Federation of Miners called for a strike across Copper Country. Government reports from the time describe hundreds of strikers, armed with sticks, stones, and metal bars threatening workers who tried to enter the mines. By the end of the month Työmies reported that 18,460 miners were on strike — more than twice the number of union members in the area.

The initial weeks of the strike were by most accounts an uplifting affair for the miners of Copper Country. Workers marched through town on a near-daily basis to drum up support and boost morale. Local chapters of the Socialist Party held picnics and rallies to raise money for the strike fund, while solidarity messages and donations poured in from unions across the country.

Leading lights of the American labor movement visited to express their support. Mother Jones, the “miner’s angel,” spoke at a mass rally in Calumet in early August and beseeched strikers to “be men, my sons, then you will make the mine bosses humble.” WFM president Charles Moyer also came to the Copper Country, as did famed labor activist Ella Reeve Bloor, whose account of the massacre on Christmas Eve would later inspire Woody Guthrie’s ballad.

The optimism these men and women must have felt was captured in a song, “The Federation Call,” penned for the occasion by a local worker named John Sullivan and published in the pro-union newspaper, Miners Bulletin:

The Copper Country union men are out upon a strike,

Resisting corporation rule which robs us of our rights.

The victory is all but won in this noble fight

For recognition of the union.

Hurrah, hurrah for the Copper Country strike

Hurrah, hurrah our cause is just and right.

Freedom from oppression is our motto in this fight

For recognition of the union.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.