by Kageyama Asako

Compiled, edited and translated by Philip Seaton1

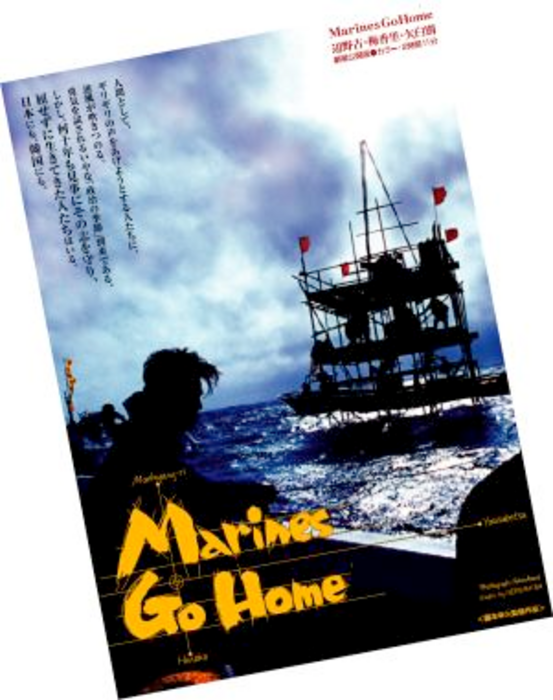

The US military’s Kooni Firing Range in the South Korean village of Maehyang-ri was closed in 2005, following a concerted effort by anti-base activists. Maehyang-ri was one of three anti-base struggles featured in the documentary film Marines Go Home: Henoko, Maehyang-ri, Yausubetsu (official website here, trailer here) directed by Hokkaido-based independent filmmaker Fujimoto Yukihisa. In this article, journalist and filmmaker Kageyama Asako (narrator and co-producer of Marines Go Home) discusses the lessons from Maehyang-ri in the context of the Futenma relocation debate that is at the heart of current US-Japan conflict.

This is part of a two-article series that considers the base relocation issue from perspectives beyond Okinawa. The other is ‘The Complete Withdrawal of the US Military from Ecuador: A Victory for Sovereignty and Peace in Latin America’ by Fuse Yūjin.

The Futenma base relocation issue has been dominating the headlines in Japan ever since the formation of the Hatoyama administration in September 2009. Understandably the focus has been on Okinawa, long the center of anti-base activism. But we should see the Futenma base relocation issue as part of a much broader problem. In this article I want to consider the Futenma issue in the context of other activities within the international anti-bases movement.

I have been involved in the anti-bases movement for many years and serve on the Hokkaido Asia Africa Latin America Solidarity Committee (HAALA). HAALA is an organization that opposes neo-colonialism, respects the rights of people to self-determination and aims for the equality of all peoples. Revocation of the US-Japan Security Treaty and the removal of all American bases from Japan are among its aims. We have links with Vietnam, Nicaragua, Cuba and South Africa among others and are involved in various humanitarian projects there. A representative of the Japan Africa Asia South America Solidarity Committee went to Ecuador to attend the anti-base activities described in Fuse Yūjin’s article [add link], and have also visited Venezuela and Bolivia.

The International Network for the Abolition of Foreign Military Bases (INAFMB) took off at the World Social Forum held in Mumbai in January 2004 and was launched officially as a result of its first international conference in Quito and Manta, Ecuador, in March 2007. I attended the Mumbai meeting as the representative of HAALA. It was an unforgettable experience. To have 130,000 people gathering from across the globe under the slogan ‘Another world is possible’ in a meeting of such diversity and vibrancy was enough to really make one believe it could happen. In particular, the demonstrations by members of India’s so-called ‘untouchables’ caste left a particularly strong impression. Their cries of ‘If another world is possible then it must include us’ brought it home that only by raising one’s voice is there any hope to change things.

World Social Forum 2004 |

Marines Go Home

In response to the calls to action in Mumbai, and also as part of the fortieth anniversary celebrations of HAALA, we started making a documentary film: Marines Go Home, Henoko, Maehyang-ri, Yausubetsu. Marines Go Home (2005, official website here, trailer here) focuses on some of the individuals and activists dedicated to the removal of US bases from three towns and villages in Japan and South Korea. In Yausubetsu (in Eastern Hokkaido), the film depicts the ‘live in protest’ of Kawase Hanji, who for many years refused to leave his home in the middle of Yausubetsu Enshujo (Yausubetsu Maneuver Area), a Japan Ground Self Defense Forces (JGSDF) firing range in Eastern Hokkaido.2 Yausubetsu is the largest training area in Japan. Each year since 1997, US marines have been coming to Yausubetsu to conduct live-fire training, all paid for by the Japanese taxpayer.3

The local struggle against the training exercises has continued for over 40 years. For many years, the Yausubetsu Peace Bon Festival was held on Kawase’s property. This festival and the Yausubetsu issue have long been at the heart of HAALA’s activities (and as such, a number of members appear in Marines Go Home). The fortieth festival was held in 2004.

In September 2003, HAALA arranged for a special guest to visit Yausubetsu to witness a US Marines Corps training exercise. Chun Man-kyu was the leading figure in the struggle to close a firing range just off the coast of Maehyang-ri village in South Korea. The American military started using the Kooni firing range there in 1951. Up until the closure of the firing range in 2005, twelve local people had been killed, either in accidents or by unexploded ordinance from the range. There was also an incident in 2000 when an A-10 fighter dropped six missiles into the sea very close to a residential area and damaged 700 houses.

Finally, the film documents the protests against the surveying work being undertaken off the coast at Henoko in preparation for the transfer and upgrading of the Futenma air base to Camp Schwab in Henoko, part of Nago city, Okinawa. The first plan in 1996 was to construct a floating heliport. This was rejected in a plebiscite in 1997. In 2002 the plan was changed to a permanent base with a runway built on a massive landfill. This plan was withdrawn after desperate protest in September 2005, only to be replaced by a new and even bigger plan drawn up by the Japanese and American governments the following month (October 2005) for a two-runway base in Henoko along the coast of Camp Schwab in Oura Bay. The deep water in Oura Bay means nuclear aircraft carriers would be able to visit. All these plans have been made in the face of stiff local opposition and would destroy a pristine marine habitat supporting among other species rare blue coral reefs and the internationally protected dugong.4 Just before the Democratic Party of Japan defeated the Liberal Democratic Party in the 30 August 2009 general election, the outgoing and deeply unpopular Aso administration signed the so-called Guam Treaty, which the US interprets as binding the Hatoyama to an agreement to build the Henoko base.5

Protestors try to prevent survey work on the proposed Henoko offshore runways site. |

Marines Go Home was released in 2005 (and an updated version was produced in 2008, official site here). A lot has happened since Marines Go Home was first released. The anti-base movement in Hokkaido suffered two keenly-felt losses in 2009 when first Kawase Hanji and then former US marine Allen Nelson6 (a staunch supporter of the ‘Marines Go Home’ message) died. With Kawase’s death, a rethinking of the strategies used by anti-base activists in Yausubetsu became necessary. The strategy could no longer be built around the theme ‘preserve Kawase’s way of life’. Thankfully, a woman who used to lodge with Kawase continues to live in the firing range, although conditions are tough. The people in and around Yausubetsu will continue the struggle, although as a vital site for the anti-bases protest movement this struggle needs as much local and international support as possible. It would be too much to ask local people to assume the whole burden of organizing activities and maintaining homes, livelihoods and places to gather within the firing range.

Kageyama interprets for the late Allen Nelson during a talk at Hokkaido University in 2007. |

Anti-base activists in Henoko have also faced a mounting struggle. As part of the planned redeployment of American forces agreed by the US and Japan in 2006, there were plans to construct deep-water port facilities at Henoko. This decision required another environmental survey, but in contrast to previous protests (depicted in the 2005 film) in which protesters canoed out to occupy the survey rigs and delay work, this time the Japan Coast Guard obstructed the protests. The Coast Guard had previously stayed out of the standoff between contractors and protestors. The level of violence used against the protestors reached life-threatening levels on occasions. Furthermore a Marine Self Defense Forces frigate was sent to the area. According to local media, the frigate had divers on board who set up survey equipment on the seabed under the cover of darkness. It was also a clear warning to protestors that the Japanese government, without any legal basis, was prepared to deploy military forces. Despite the risks, the protests have continued on land and at sea.7

The protestors also faced a split in the anti-base movement during the 2006 Nago mayoral elections.8 That election was won by the LDP-Komeito-backed Shimabukuro Yoshikazu, who supported the construction of the base. The anti-base movement vote was split between two anti-base candidates, both of whom were city councilors: Oshiro Yoshitami and Gakiya Munehiro. Gakiya was supported by the Social Democratic Party, Communist Party, Okinawa Social Mass Party, Democratic Party and the unions, but had voted for the move from Futenma to Henoko in 1990, so many opponents of the base felt unable to support him.

After the 2006 election, the number of people in the tented camp dwindled in the face of the confusion over the mayoral race and the violent tactics being used against protestors. In the midst of all this, the leader of the Inochi wo Mamoru Kai (Saving Life Society), Kinjo Yuji passed away. It was a tough time, yet the movement survived.

The anti-base movement was brought together again with the January 2010 election of Inamine Susumu as mayor of Nago on an anti-base ticket.9 Earlier there had been change on the prefectural level: at the 2008 Okinawa Prefectural Assembly elections, LDP-Komeito lost its majority, allowing the assembly to pass a resolution opposing construction of a new base on 18 July 2008.10 Then during the 2009 general election, the LDP-Komeito coalition lost all its parliamentary seats in Okinawa. This was a backlash against the government on the bases issue, and also over the deeply unpopular healthcare reforms adversely affecting the elderly. The new extent of unanimity in Okinawan opposition to the Henoko plan was demonstrated on 24 February 2010 when ‘Okinawa assembly members voted unanimously to adopt a written request urging the central government to relocate the Futenma base outside the prefecture.’11

With the exception of the governor, the entire Okinawan leadership was now in the hands of anti-base forces, and even the Governor has faced tremendous pressure to reject the Henoko plan. Following the wave of optimism that accompanied the victory of the Democratic Party of Japan in the August 2009 elections on a specific pledge to move bases outside the prefecture, or outside of Japan, serious doubts have arisen about the base decision. In the face of intense US pressure, the DPJ is actively exploring alternative base sites including Henoko and other Okinawan islands as well as on mainland Japan and in Guam. Of course, even if the Hatoyama administration succeeds in honoring its election pledge to move Futenma out of the prefecture or out of Japan altogether, this would not be more than a slight dent in the US military presence in Japan: at present (March 2010) comprising 85 facilities covering 77,000 acres of land, and numbering 36,000 on-shore personnel and 11,000 personnel afloat.12 Nor would this halt the increased integration of US and Japanese military forces, a process which is accelerating. The US military continues to conduct live-fire exercises in Yausubetsu. Indeed, the majority of SDF facilities are used jointly by the Japanese and US militaries on a daily basis, as are a number of civilian facilities such as ports and airports.

Marines training with GSDF soldiers at Yausubetsu, March 2008. |

So while all attention is focused on Futenma, what is actually occurring is the ‘Okinawaization’ of Japan. As former marine Allen Nelson has testified, during the Vietnam War Okinawa was used as a training location for soldiers en route to Vietnam.13 This role seems to be being extended across Japan. The political need to reduce the burden on Okinawa was the underlying reason for the relocation of US Marine Corps live fire drills from Okinawa to Yausubetsu in 1997, and those ‘skills’ practiced in Hokkaido have been exported to conflicts in other parts of the globe. As Saito Mitsumasa has demonstrated, the Misawa base in Aomori has long been a key part of the projection of US nuclear strike capability in Asia, which makes a mockery of Japan’s three non-nuclear principles (as does the much more public revelations of the ‘secret pacts’ during the Cold War to allow nuclear weapons into Japan, which was officially acknowledged by the DPJ government in March 2010). Furthermore, Misawa is currently being used as a forward staging area for bombing missions in Iraq and Afghanistan.14 These developments illustrate that US forces are not in Japan for the protection of Japan or peace and stability in Asia, but for the projection of American power throughout Asia and the Pacific, even to the Middle East.

Learning from Maehyang-ri

In the context of the Futenma base clash there are many lessons to be learned from the successful campaigns in Maehyang-ri to shut the firing range. Of course there are some important differences between Japan and South Korea, too. But we can summarize the keys to success as follows.

A helicopter gunship blasts an island off the coast of Maehyang-ri. |

The first is the political background, namely the democratization of South Korea in the 1980s, and particularly following the 1987 presidential election after years of military dictatorship. Citizen’s groups mushroomed, and the anti-base group in Maehyang-ri was founded in 1988. Previously, any opposition to the base risked repression as a ‘North Korean spy’. The Maehyang-ri struggle was an integral part of the democratization process.

Even so, and this is the second point, citizens showed great resilience in the struggle. Despite democratization they still faced repression and intimidation. In November 1988, local residents demanded the removal of the base. In protest they occupied the base and tried to prevent the live-fire exercises. They occupied the base again in 1989 and risked their lives to stop the exercises.

In response the American military forbade entry to the base. In retribution they dumped four trucks worth of sand on Chun Man-kyu’s fields. When irate local people tried to occupy the base, 50 people including Chun were arrested. Then in 2000 after the incident in which an A-10 plane dropped its payload causing damage to many homes, the US military continued training as if nothing had happened. This triggered widespread protests across the country. Around 40,000 police were deployed. They arrested 100 protestors, including Chun, and 500 people were injured in clashes. Despite all these trials, the protest movement persevered until it was eventually able to get the base closed in 2005. The role of direct action was vital, as was the resilience people showed in the face of the risks that direct action entailed.

Chun Man-kyu inspects the ordinance littering the beach of Maehyang-ri. |

Third, international solidarity in the anti-base movement was also vital. Chun’s active development of links with groups in other countries (Marines Go Home shows him on his September 2003 visit to the Yausubetsu firing range meeting Kawase Hanji) raised the profile of Maehyang-ri. It became a rallying call for the anti-bases movement, alongside the campaign to stop US navy live-fire exercises on Vieques, Puerto Rico.

In fact, the Maehyang-ri protestors learned one of their most effective strategies from Japan. In Yokota, for many years Japanese citizens had been filing lawsuits against the US military and Japanese government on the basis of noise pollution caused by US jets using the base. In 1998, 15 residents of Maehyang-ri filed similar suits, which ended in victory in the courts in 2003. The base was breaking Korean law regarding the levels of noise pollution, so local people had “a real case to present to the government”.15 The verdict pronounced for the first time that the noise pollution from the American base was unlawful. Each plaintiff was awarded about 10,000 dollars in damages. Following this, in 2001 a further 2,000 plaintiffs sued the Korean government. The ruling in December 2004 ordered the government to pay total damages of 10 million dollars.

The legal victory over noise pollution at Maehyang-ri has a counterpart in the lawsuit filed in San Francisco that the construction of the Henoko base would violate the National Historic Preservation Act. The court found in favor of the plaintiffs in January 2008.16 This should have provided the appropriate legal barrier to the Henoko base issue, although the US and Japanese governments forged ahead in signing the Guam Treaty in 2009, which is an agreement to do something already declared illegal by the courts.17

But, as in the Henoko case, we cannot decontextualize the Maehyang-ri campaigns from broader US military strategy. The current US strategy in South Korea stresses the creation of ‘hub bases’. The Maehyang-ri firing range may have closed, but farmers have been evicted from their land around the Songtan Air Base (also known as Osan Air Base) and the army base Camp Humphries in Pyeongtaek to expand the bases there. This occurred during the presidency of President Roh Moo-hyun, a lawyer and central figure in the democratization movement.

The Pyeongtak struggle was fierce. In 2005 around 200 farming households were thrown off their land under a compulsory land acquisition order. Having been removed from their land they also lost their livelihoods. The farmers and their supporters continued to resist, but the Korean government deployed 10,000 police and 1,000 troops. They cordoned off the villages and moved in heavy equipment to destroy the farmland and buildings. The final villagers were forced to leave in April 2007.18

This is not to say that the Kooni firing range in Maehyang-ri was shut down because it was unnecessary: it had often been called the best firing range in Asia by the US military. Ultimately, Maehyang-ri was breaking Korean law and untenable in the face of local opposition. But when it was shut down, training was simply shifted to other South Korean facilities, Alaska, Okinawa or elsewhere. Bases will not be returned because they are ‘not needed’. Neither is it a question of saying that a base can be closed when an alternative is found. Anti-base forces are not interested in saying ‘not in my back yard’. We are saying ‘not in anyone’s back yard’ to the over 1,000 overseas bases that the US military maintains throughout the world.

A Global Struggle

In 2005 I attended the fifth World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, Brazil. I showed a 15-minute segment of Marines Go Home (at the time still under production). It was not easy to screen the film outside in a tent, or to give the accompanying talk in English, but it was warmly received. A Korean woman asked me to explain more about the Henoko struggle, Indian and American participants shook my hand, and a person from Iraq pointed out that ‘Marines Go Home’ is a slogan there, too. I really felt as if the messages of Kawase Hanji, Chun Man-kyu and all the activists in Henoko were resonating elsewhere.

It is all too easy to see base struggles in isolation, but in reality there are similar issues in many places. Japanese people are often surprised to learn that anti-base protests exist in the US, too. In 2006 I spent a lot of time in the US collecting materials for our next film, America Banzai: crazy as usual (official site here). With colleagues in the Southwest Workers Union (who I had met through WSF), I learned about the fight against the environmental damage and noise pollution caused by the Kelly Air Force Base (since 2001 the Kelly Field Annex, part of the Lackland Air Force base in San Antonio, Texas). The base had handled nuclear and chemical weapons. Waste was just dumped into local creeks causing serious health problems from cancer to birth defects. Local residents protested on numerous occasions to the air force and US government. Only after Kelly Air Force base closed were the causes of the health problems partially disclosed, but the air force and government never admitted any responsibility or compensated residents.

Some of those activists appeared in America Banzai. In 2009, a number of people who had appeared in America Banzai visited Japan to take part in a speaking tour to similarly affected places in Japan: Kanagawa, Iwakuni and Okinawa. The discussions of the damage caused by the Kelly Air Force base made quite an impression. Many Japanese think that the base issue exemplifies an American double standard by which things that would not be permitted in the US are forced onto Japan. This is not the case. Both countries suffer from the same problems. Whether in Japan, South Korea or the US, the fundamental problem is the government and military riding roughshod over local people. One senses, however, a heavy element of racism and discrimination surrounding the bases issue. In the case of Kelly Air Force Base, most local residents were poor Mexicans. Laws, it seems, are adhered to more closely when the people harmed by the bases are not the poor, indigenous peoples, immigrants, Japanese, Koreans or others.

Given the complexity of the bases issue, there is little reason for confidence that President Obama and Prime Minister Hatoyama will bring much ‘change’, despite the moods of public optimism following the launches of their respective administrations in 2009. However, Prime Minister Hatoyama’s decision to delay a final verdict on the Futenma base has at least provided a chance to increase discussion of the bases issue in the Japanese media. What has ensued is a major power struggle between popular local opposition to bases and the powerful vested interests promoting them. One can only hope that come May, when Prime Minister Hatoyama announces his decision, he chooses the will of the Okinawan people over the demands of the US. After all, would that not be fulfilling the ideals that America has so frequently used as an excuse to go to war: the spread of democracy, and the respect for the will of the people that democracy entails.

Kageyama Asako is a Hokkaido-based journalist and filmmaker. In addition to Marines Go Home, she has been involved in three films shot in the US: 「アメリカばんざい Crazy as Usual」 (English title God Bless America), 「アメリカ – 戦争する国の人びと」 (English title God Help America) and 「One Shot One Kill – 兵士になるということ」. Details on all these films are available here. To order the films, email morinoeigasha@gmail.com

Philip Seaton is an associate professor in the Research Faculty of Media and Communication, Hokkaido University. An Asia-Pacific Journal Associate, he compiled this article for the Journal. He is the author of Japan’s Contested War Memories and translator of Ayako Kurahashi’s My Father’s Dying Wish. Legacies of War Guilt in a Japanese Family. His webpage is www.philipseaton.net

Recommended citation: Kageyama Asako and Philip Seaton, “Marines Go Home: Anti-Base Activism in Okinawa, Japan and Korea,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 14-1-10, April 5, 2010.

Notes

1 The article has been compiled through correspondence between Kageyama Asako and Philip Seaton. We are grateful to Mark Selden for his helpful comments.

2 See Tanaka Nobumasa, ‘Defending the Peace Constitution in the Midst of the SDF Training Area’.

3 “[Live-fire] training has been conducted on mainland Japan since the governments of Japan and the United States formally agreed to cease the firing of artillery on Okinawa in 1996. Fire maneuver areas were chosen on the mainland for artillery training exercises at Hijudai, East and North Fuji, Ojojihara and Yausubetsu. The signed agreement requires the Japanese government to fund all additional expenses not incurred when firing on Okinawa, such as transportation of personnel, equipment and barracks facilities.” Leatherneck, ‘3/12 Marines rain steel at Yausubetsu’.

4 For a detailed history see Gavan McCormack and Matsumoto Tsuyoshi, ‘Okinawa Says “No” To US-Japan Base Plan’ and Gavan McCormack, ‘The Travails of a Client State: An Okinawan Angle on the 50th Anniversary of the US-Japan Security Treaty’. For updates on the anti-base struggles and US-Japan negotiations over the closure of the Futenma Base and the construction of a new base see numerous entries at the Peace Philosophy Centre.

5 Gavan McCormack, ‘The Battle of Okinawa 2009: Obama vs Hatoyama’.

6 Allen Nelson’s story is described in Philip Seaton, ‘Vietnam and Iraq in Japan: Japanese and American Grassroots Peace Activism’.

7 For more on the protests, see Kikuno Yumiko, ‘Henoko, Okinawa: Inside the Sit In’. See also the 2008 version of the documentary film Marines Go Home.

8 See Urashima Etsuko, ‘The Nago Mayoral Election and Okinawa’s Search for a Way Beyond Bases and Dependence’; The Japan Times, ‘Base moderate elected Nago mayor’, 23 January 2006.

9 See Urashima Etsuko and Gavan McCormack, ‘Electing a Town Mayor in Okinawa: Report from the Nago Trenches’.

10 Gavan McCormack and Matsumoto Tsuyoshi, ‘Okinawa Says “No” To US-Japan Base Plan’.

11 The Japan Times, ‘No head-start base talks with U.S.’, 25 February 2010.

12 This data accessed on 24 March 2010 from U.S. Forces Japan.

13 Philip Seaton, ‘Vietnam and Iraq in Japan’, The Asia-Pacific Journal.

14 Saito Mitsumasa, ‘Mission Impossible? Misawa as the Forward Staging Area for the Secret US-Japan Nuclear Deal and the Bombing of Iraq’. On secret pacts, see The Japan Times, ‘Secret Pacts Existed; denials “dishonest”’, 10 March 2010.

15 South Korean Defense Analysis Official, interviewed by Andrew Yeo, ‘Local Dynamics and Framing in Korean Anti-Base Movements’, Kasarinlan: Philippine Journal of Third World Studies 2006 21 (2): 34-60, page 54.

16 For more on the lawsuit see Miyume Tanji, ‘U.S. Court Rules in the “Okinawa Dugong” Case: Implications for U.S. Military Bases Overseas’, Critical Asian Studies 40:3 (2008), 475-487.

17 See Gavan McCormack, ‘The Battle of Okinawa 2009’, The Asia-Pacific Journal.

18 For more on Pyeongtaek, see Andrew Yeo, ‘Local Dynamics’, Kasarinlan.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.