From Jacobin

A New International Left-Labor Network

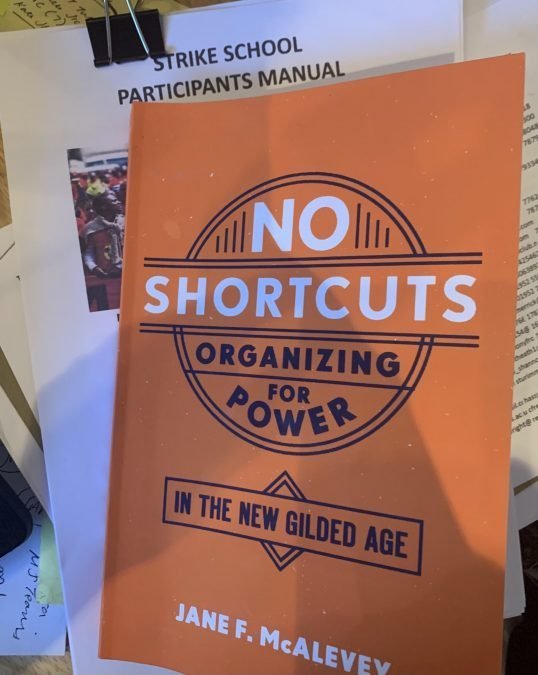

What set Strike School apart from other trainings was not only its content but its ambitious scope. Thousands of activists from seventy countries, were brought together across industries, unions, and national borders.

For months, dozens of unionists from across the world worked with McAlevey and the RLS to plan the content and format of Strike School, cohering in the process the first steps of a horizontal transnational network of left-labor organizers. For the training itself, over a hundred twenty volunteer facilitators led the smaller interactive break-out groups through which participants were able to discuss methods and practice skills.

“The practice helped us identity mistakes we make so that we can do our best to avoid them when we go back into the field.” explained Bora Mema, an activist currently organizing support for striking oil-refinery workers in Albania.

To allow for global participation, the course was held twice daily and all material as well as trainings were translated into Arabic, Spanish, French, Portuguese, and German. A list of international unions and organizations that ultimately participated in the school includes, among others, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa, the Palestinian Postal Workers, the Ghana Registered Nurses and Midwives Association, the Jordan Teachers Union, New Trade Union Initiative in India, E tū in New Zealand, Sinsaúde and the Sindicato dos Enfermeiros in Brazil, Red de Solidaridad con Trabajadorxs en Riesgo in Mexico, Fedotrazonas in the Dominican Republic, the University and College Union in the UK, the Algemene Onderwijsbond in the Netherlands, and numerous organizations from the United States and Canada.

Unions were not the only groups that took part. Also participating were numerous tenants groups, the National Students Federation of Pakistan, the Center for Migrant Advocacy in the Philippines, Comité Fronterizo de Obreros in Mexico, Fridays for Future in Germany, Agir pour la Paix in Belgium, Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca in Spain, Core in Nigeria, as well as the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee in the United States.

Since the chance to exchange organizing experiences across national borders is so rare, the international breakout group sessions were a highlight for many. And despite differences in national contexts across the globe, participants generally said that the methods taught in Strike School were relevant for their particular countries.

Nisreen Haj Ahmad, one of the eight course participants from the organization Ahel — which coaches social justice groups in Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan — explains that the course “opened our eyes to the degree of discipline and detail orientation needed when organizing a union or a strike.” For Randy Miranda of the Partido Manggagawa another takeaway was the utility of “big bargaining”:

Here in the Philippines, it’s a common practice by unions to have collective bargaining negotiations done by only a small group, usually the president and some officers only, who rely more on the wisdom of lawyers sitting with them in the negotiation. But we learned in Strike School about the importance of getting a larger number of workers engaged in collective bargaining. The lesson is: trust the workers, especially during negotiations.

In some regions, a tradition of serious labor organizing has had to be recreated from scratch. This was the case in Albania, where Bora Mema’s Organizata Politike lends organizing support to workers founding independent unions in garment, oil refining, mining, and call centers: “Albania has faced massive privatization and a lack of trade unions since the fall of the socialist regimes, which is why in our country its so important to restart organizing. Particularly because we’re lacking any tradition, learning from the school has been more than welcome.”

When asked about the main lesson she took from the course, she replied that “everything was important, but first thing that comes to mind was a small-but-important point: it’s not only about ID’ing the leader in a workplace, but also about figuring out who is the first person you should approach who can bring the leader on board.”

The logistics of making space for thousands of people across the world to participate in an interactive training were daunting. One of the significant novelties of the course was the way it effectively harnessed new technology to promote old organizing techniques. While Strike School focused on face-to-face organizing methods that go as far back as the 1930s, the organizational structure of the training itself — with its reliance on digital tools and volunteer labor to scale up beyond the capacities of paid staffers — resembled the new “distributed organizing” model utilized by Bernie Sanders’s 2016 and 2020 campaigns, the Sunrise Movement, and the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee in the United States.

Though the jury is still out whether a “distributed” model can effectively promote organizing (rather than just mobilizing), the experience of Strike School itself suggests potential for rebuilding a robust labor-left infrastructure.

Since McAlevey and the RLS will be offering more international training courses in 2021 and beyond, two issues merit further consideration down the road. The first is how to further internationalize the training’s content and network, particularly to better reflect the Global South. Though significant strides were made in this regard, all organizers agreed that Strike School’s plenary speakers and participants were still disproportionately Anglophone and European.

Beyond efforts to deepen outreach to labor unions and organizers in Asia, Africa, and Latina America, this challenge also poses the thornier question of how effective organizing methods can take on distinct forms in different political contexts.

For instance, because the legality of union activities and the level of repression varies significantly between countries, how might this shape organizing approaches? The particularly harsh realities of organizing in the Global South was hammered home during Strike School itself when a group of union member participants from Nigeria were arrested for their organizing efforts. Digging further into how methods can be “tempered” for specific countries — as well as specific industries — is an important question that could benefit from more international exchange and deliberation.

The second looming issue is how these organizing methods can help build class power in the political arena. Forging strong, strike-ready unions is urgently needed, but history indicates that there’s only so far working people can go without independent parties to represent their interests. To what extent, and in what ways, can the methods taught in Strike School be translated into political organizing?

It’s hard to imagine reversing neoliberalism, let alone winning a true political and economic democracy, without rebuilding political parties of and for the working class. But this poses a whole series of strategic tensions. How to balance shop-floor organizing with electoral work, and how to push for elected representatives to promote (rather than dampen) bottom-up action have long been thorny political dilemmas for leftists.

Answering these questions might lie beyond the scope of a training course. But over the coming years, the promising international network emerging around Strike School could play a significant role in figuring out how to effectively combine organizing in workplaces and neighborhoods with organizing inside the state.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.