by Valerie Wieskamp –

It has become almost a requirement in American culture that people talk about “supporting our veterans”. But this is what our soldiers do-they invade, they rape, they silence.

Not every soldier, of course. But militarism embraces violence, and no- our soldiers have not died defending our freedoms. They have died defending our right to go anywhere, steal their resources, destroy their lives and livelihoods, rape their women, claim it all for the good old USA. Apologists, too many who claim to be feminists, say we are fighting to free women from Islamic oppression.

In French we call this bullshit.

Of course our soldiers too are victims of American exceptionalism and brutality painted over to look like humanitarianism. And many of these women and men, if they have escaped with their lives and the realization they they have been playing the role of oppressor, become fighters for peace and social justice. Against wars of conquest and against rape and all other forms of dehumanization. -Ed.

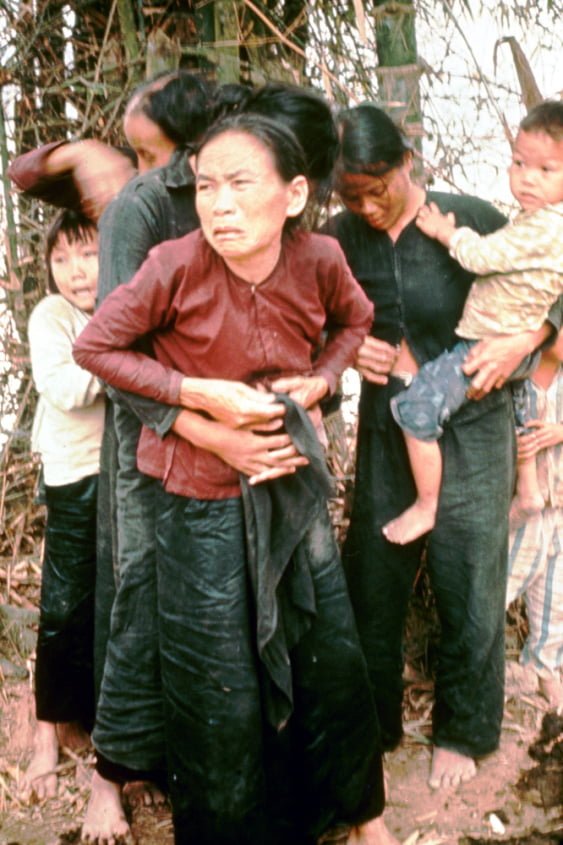

Looking back at the Vietnam war and the iconic photographs that mark that era, how is it that the American public knows about the “Napalm Girl” but no one knows or speaks of the My Lai “Black Blouse Girl?” And what does it mean that, forty-five years later, even though her experience was publicized by investigative reports and Congressional testimony, what happened to her – reflected in this famous photo – remains hidden in plain sight?

The My Lai Massacre captured public awareness largely due to the 1969 public release of graphic photographs taken by Army Photographer Ronald Haeberle. Since the release, viewers have been captivated by the visceral emotion expressed on the face of the woman in the foreground of the photo below (published in 1969 by Life magazine). According to Life’s caption of the photograph, these villagers were “huddle[ed] in terror moments before being killed by American troops at My Lai.”

While the My Lai Massacre is widely recognized as a military atrocity and an act of mass murder committed on civilians and non-combatants, true appreciation of the event as an act of mass rape and sexual abuse has never clearly materialized in the American consciousness, in spite of public data and testimony shortly after the massacre happened. Media presentation of the photograph of the Black Blouse Girl mirrors this amnesia.

By reading the image closely, you can see that the teenager in the right background is buttoning up her blouse. It’s a curious action. Why would she be preoccupied with a button while the other people in the photograph were terrified of being killed? Why was the button undone to begin with?

Testimony from the 1969-1979 Peers Inquiry solves the mystery of the button: the image actually captures these women and children in the moments between a sexual assault and mass murder. In his inquiry testimony, Haeberle explains that a group of soldiers were trying to “see what she was made of,” and that they “started stripping her, taking her top off,” Additional testimony from the investigation confirms this.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.