From Jacobin

Your first chapter focuses on the post-revolutionary period and the importance for the young Soviet state for building ties with the colonial world. The Bolsheviks organized events like the Baku Congress of the Peoples of the East (1920) and established institutions such as the Communist University for Toilers of the East (KUTV, 1921–1938). But how important were cultural issues in these efforts?

In a sense, the first phase of Soviet engagement with the colonial world, in the interwar period, was more significant than the second, which began with the 1955 Asia-Africa conference in Bandung. I say that even if the Soviet investments in supporting independence movements and newly decolonized states were incomparably greater during the latter phase.

One can find plenty of fault with the anti-imperialism of the Bolsheviks even in the interwar period: a good deal of paternalism toward those being emancipated and a highly “stageist” understanding of history; there was a growing great-power logic, and constant about-faces. But it is worth remembering that in the interwar period the USSR was the one country that not only verbally denounced imperialism but put a lot of money where its mouth was.

Even accepting existing critiques of Bolshevik intentions and concrete efforts regarding the colonies, the October Revolution itself had an immense effect on the colonial world. There, it was interpreted not so much as an anti-capitalist revolution (as it was in the West) but as an anti-imperial uprising and thus a major inspiration behind such movements as the May 4 movement in China, Rowlatt Satyagraha in India, the 1919 Egyptian Revolution, and much anti-colonial activism in subsequent years.

As a deliberate component of these early Soviet anti-imperialist initiatives, literature and film played a relatively minor role: after all, the networks that extended between the USSR and the colonial world were primarily clandestine, and these offered little space for culture.

Nevertheless, Russian/Soviet texts did trickle into colonial societies, often via circuitous routes and multiple translations. Whether written before or after 1917, they came with the halo of the Russian Revolution, symbolically gesturing to a modernity alternative to that of the West. The colonial intelligentsias reading these texts interpreted them to suit their particular anti-colonial, nationalist struggles.

How did the Soviet interest in the colonial world change over the 1930s?

What changed was the consolidation of Stalinism as well as European geopolitics. Much of the interwar-era anti-colonial work was enacted within the Comintern, the Eastern Secretariat of its Executive Committee, and affiliated institutions such as the League against Imperialism and KUTV.

Upon its first appearance in 1919, the Comintern was rather distinct from the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs (the Soviet foreign ministry). Its support for communist organizing in Britain and France, for example, and anti-colonial uprisings in their colonies, ran at cross-purposes with the diplomatic efforts of the Soviet state to secure major European powers’ recognition.

By the 1930s, however, Stalinism had reduced the Communist International to an instrument of Soviet foreign policy. While the Comintern was formally closed down in 1943, most likely as a good-will gesture to the Allies, its activities had been permanently debilitated since the purges of 1937–38, during which an extraordinary large proportion of its Moscow-based personnel, including from the Eastern Secretariat and its affiliated structures, was executed, arrested, or dismissed. By the late 1930s, Moscow had lost many of the resident communists hailing from the colonial world, as well as much of its network and expertise regarding Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

There were also international factors. As Fredrik Petersson shows in his history of the League against Imperialism, the Nazi takeover in Germany in 1933 resulted in the League’s loss of its Berlin headquarters, from which it never recovered. The communist adoption of a broad anti-fascist Popular Front in response to the rise of Nazism further harmed anti-colonial internationalism.

While this policy has been often hailed as a success in Europe and the United States, as far as anti-colonial activists were concerned it effectively meant the USSR allying with the main imperialist powers against Germany — and hence disinvesting from their cause. As a whole, the expectation of a European war shifted the Soviet leadership’s interest away from anti-imperialism.

Did the Bandung Conference in 1955 change the way the Soviet state understood the colonial world?

Only after Stalin’s death and the slow beginning of de-Stalinization could the Soviet state re-enter the realm of anti-colonial politics. Before that, even major events such as the decolonization of the Subcontinent in 1947 were barely addressed in late-Stalin-era foreign policy. The emergence of an independent India and Pakistan was treated as formal tweaking within the capitalist world order rather than the beginnings of a new and potentially non-capitalist Third World.

The Bandung Conference, which heralded that world’s arrival, startled the Soviet foreign policy establishment into action — prompting a renewed investment in anti-colonial politics. But the two-decade gap between the first and the second phase of Soviet anti-colonial politics — and their zigzags — had alienated many independence movements from Moscow.

Moreover, by now the USSR had lost its monopoly on anti-colonial and anti-racist discourse: that was coming from many quarters and especially from within the Third World project, which became the main moral voice against colonialism.

In addition to Soviet loans, economic aid, experts, and military support, this second phase of Soviet anti-colonialism included a major cultural component. This included a massive program for translating literature from Asia, Africa, and Latin America into Russian and other Soviet languages, and active courtship of writers and filmmakers from these continents.

As an heir to the nineteenth-century Russian intelligentsia, the Soviet state, down to its bureaucracy, was culture-centric, believing in the capacity of culture and especially literature, to change people’s minds and even whole societies. Fantastically, it extrapolated this belief to societies with vastly different traditions and structures.

By the logic of the Cold War, this investment had to be reciprocated by the Western side. Never before (or after) had the CIA been caught supporting literature; during the 1950s and 1960s, it subsidized a whole empire of literary magazines across five continents. As Monica Popescu and other scholars have shown, this investment transformed the structural circumstances of postcolonial literature.

For all the devastation the Cold War brought to Africa, Asia, and Latin America, writers from these continents were some of its main beneficiaries — and so, too, were readers, as the Soviet bloc and the West tried to distribute “their” texts as widely (and hence, cheaply) as possible.

In October 1958, important figures like W. E. B. Du Bois, Nâzim Hikmet, Mao Dun, and others met in Tashkent for the Afro-Asian Writers’ Congress. Why was it important to organize this event in the Uzbek capital? How far were the participants aware of each other’s writings?

The choice of Tashkent as the setting for the inaugural congress of the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association (and ten years later, for the biannual Tashkent Festival of African, Asian, and Latin American film) was a very deliberate move by the Soviet cultural bureaucracies.

A city showcasing both the successes of Soviet development and powerful local historical traditions, Tashkent positively impressed even delegates not inclined to sympathize with the Soviet project. They were seeing not another European metropolis — as they would have, if the event been set in Moscow — but a highly diverse and primarily non-white society.

Thus, from the late 1950s till the end of the Cold War, Tashkent (and to a lesser extent, Alma-Ata, Samarkand and Bukhara, Erevan, Baku, and Tbilisi) figured disproportionately on the itineraries of African and Asian cultural delegations to the USSR.

One recurrent theme at the first Afro-Asian Writers’ Congress and the film festivals held in Tashkent was the participants’ amazement at having to travel there to meet one another. If they were aware of the nuances of Western literature or cinema, they had little knowledge of the processes taking place in neighboring African or Asian or Latin American countries. Peripheries, after all, don’t talk to each other. The ambition of the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association and the Tashkent Festival was, indeed, to challenge these countries’ status as Western cultural peripheries, by building on such interconnections.

How was Third World cultural production received in the USSR?

That’s actually a somewhat sad part of the book’s story. Literature from Africa and Asia was extensively translated by Soviet publishing houses, but could not rival the popularity of Western texts. I came across a number of Soviet-era copies in Russian libraries in completely virgin state, with pages uncut. Especially for the Western-centric late-Soviet intelligentsia in Moscow and Leningrad, Real Literature could only come France, England, Germany, and the USA — any text originating from Africa or Asia was a priori inferior.

There were exceptions: the Latin American boom novel enjoyed immense popularity in the USSR after it had received Western imprimatur, and so did Japanese literature. Several writers such as the Turkish poet Nâzim Hikmet and his compatriot, the satirist Aziz Nesin, enjoyed genuine, grassroots popularity among Soviet readers.

Also, influential as it was in forming popular opinion, the intelligentsia in Russia’s two capitals was not the entire Soviet readership: there were a number of people genuinely interested in decolonization and specialists in the field. Anecdotally, readers from Soviet Central Asia or the Caucasus were particularly interested in literature from neighboring countries: Azerbaijanis in Turkish literature, Tajiks in Iranian literature, and Uzbeks in texts from Afghanistan and India.

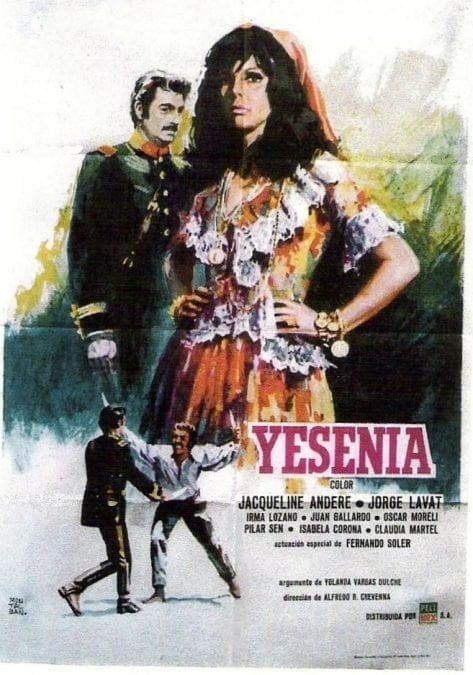

With cinema, the story is somewhat different: certain non-Western cinemas, such as India’s, enjoyed immense popularity with Soviet viewers. Three of the twenty-five films most watched on Soviet screens (from any country, including the USSR) hail from India, and there is one from Egypt, The White Dress (1975). Topping this list, with оver ninety million viewers, is the Mexican melodrama Yesenia (1971).

The genre here is key: as the USSR produced few melodramas and imported even fewer from the West, the main source of this most popular of genres, as far as Soviet viewers were concerned, was non-Western cinema.

At the same time, Third Cinema — political consciousness–raising cinema, which we associate with the documentaries produced and screened in underground conditions by Latin American filmmakers such as Argentinia’s Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas, or the legal but still revolutionary fiction films of Mrinal Sen in India and Sembène Ousmane in Senegal — was not at all popular with Soviet audiences.

This lack of mass audience interest is partly understandable: this genre is itself much less popular than melodrama. The USSR sometimes bought a couple of copies of political films (essentially playing in two to three cinemas in Moscow) as a diplomatic gesture toward some important leftist filmmaker. But often, they did not even do that. Preferring to work with states rather movements, the late Soviet state was suspicious of guerrillas, whether holding rifles or cameras.

Did the attempt to create a “Soviet-aligned Third World literary field” work? What consequences did it have on Third-Worldist authors’ writings?

We usually tend to imagine the Cold War as a contest of two equal forces. But this not only erases various Third World forces, but also exaggerates Soviet capacity compared to the West. Even at its peak, the Soviet economy represented only half that of the USA. Nor were Eastern Bloc states economically a match for Western Europe.

Moreover, the colonialist networks the United States, Britain, France, Portugal, and Belgium had developed, and the languages and the schooling they had imposed, made the newly decolonized societies structurally dependent on them in the field of literature, among others.

Western domination in the World Republic of Letters has been quite stable for the last two centuries. While backed by the moral capital of the newly assertive Third World and the material support of Soviet cultural bureaucracies, this effort to forge a literary field encompassing the Soviet Bloc and the Third World faced much more powerful forces. Thus, just like the attempt to create a unified political or economic Third World via import-substitution industrialization, South-to-South and South-to-East trade and political alliances against the West, it was eventually defeated.

Nevertheless, these efforts were not without consequences. That Indian audiences could read African literature and vice versa, and that writers from the three continents imagined themselves part of a single cultural front, owed to the work of the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association, its congresses, its translation initiatives, its literary prize and its multi-lingual journal.

Postcolonial scholarship has already accounted for the literary nation-building in which narratives from Africa, Asia, and Latin America engaged during this period. In addition, a number of authors from these continents expressed international solidarity with other Third-Worldist forces or gestured toward distant utopias such as the USSR (or China).

Through subgenres such as the Latin American supply-chain novel — connecting mines and plantations with the corrupt politicians in their capitals and boardrooms in Chicago and New York — this Third-Worldist literature sought to imaginatively situate its reader within a broader world-system.

Tashkent also hosted the First Festival of African and Asian Film. How important was cinema in these cultural connections?

When asked about his switch from novel-writing to filmmaking, Sembène Ousmane often invoked the illiteracy in his native Senegal, which stood in the way of postcolonial writers’ ability to address their own peoples. He called cinema “Africa’s evening university.” Soviet cultural bureaucracies gradually reached a similar conclusion. But there was also another factor behind their work to expand Soviet cinematic networks to Africa, Asia, and Latin America, which distinguished this effort from their promotion of Russian or Soviet books abroad: profits.

Much more than literature, the earnings of Soviet films abroad (or the box office of foreign films on Soviet screens) mattered to Soviet bureaucracies. Sovexportfilm — the Soviet monopolist on buying and selling films abroad — was for most of this period a branch of the Ministry of Trade.

Nevertheless, Western — particularly, Hollywood — domination was even greater in the global cinematic field than in literature. As Sembène and Sovexportfilm discovered, it was very hard to show a non-Western film in Senegalese cinemas. The solution proposed by the African, Asian, and Latin American filmmakers who gathered every two years from 1968 at the Tashkent Film Festival, was to nationalize the entire national film industry, from production to distribution.

As the main Third World film festival, Tashkent was important in familiarizing filmmakers from the three continents with each other’s work, and more specifically, in internationalizing Third Cinema beyond its Latin-American core.

How influential was the Soviet film on Third Cinema? How come Latin American filmmakers decided not to follow the path of Sovietism?

By the 1960s, the USSR had lost much of its luster as a revolutionary force in the eyes of many Third-Worldist radicals. Depending on how confident and strong they were, even pro-Soviet communist parties were increasingly willing to challenge it, seeking to better correspond to their own realities. Many leftists were looking elsewhere for inspiration: at certain times and in certain geographies, China or Cuba seemed to be where the revolution was really at.

Moreover, if their struggle against neocolonialism — their independence — was to be worth anything, they couldn’t simply look up to another superpower for instructions. So, most Third Cinema filmmakers, especially in Latin America, where the movement originated, refused to pay tribute to Moscow in their films or public statements.

Still, it is hard — if not impossible — to produce engaged cinema without making some reference to the Soviet cinema of the 1920s, to Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov, and the many others who helped develop the grammar of political cinema.

One particular genre whose evolution I studied from the early Soviet period (Dziga Vertov, Roman Karmen) to Third-Cinema filmmaking in Latin America, was the solidarity documentary film. The connections are there. And yet, as Masha Salazkina has shown, some Latin American filmmakers denied seeing Soviet films from the 1920s or reading Soviet film theory, even when they most likely had.

Did this interest in Third-World literature and cinema continue after the collapse of the Soviet Union?

No. Among other things, the end of the Soviet bloc around 1990 meant the region’s reintegration into the Western-dominated literary and cinematic world-system. In this new, unipolar world, there was little place for the cultural flows that had once connected the former Second and Third Worlds.

Looking at Moscow’s bookstores today, it is impossible to imagine that thirty-five years ago they were selling a great many Soviet translations of African and Asian literatures. In Russian cinemas (before the pandemic), even Indian films are completely gone — the domination of Hollywood is near-total.

Today’s Russian expertise in African, Asian, and Latin American studies is a fraction of the knowledge the Soviet-area studies apparatus had generated. For my research, I read multiple volumes of Soviet-era scholarship on African cinema. I can confidently say that not a single person works in that field in Russia — this, even though African cinema has grown significantly since then, not least thanks to the work of a number of Soviet-educated filmmakers such as Sembène, Souleymane Cissé, and Abderrahmane Sissako.

With the disappearance of Soviet censorship during perestroika, what used to be a marginal view voiced only by a fraction of anti-Soviet dissidents — that the Third World was a backwater holding “us” back from joining the family of civilized Western nations — became a trope among the new generation of democratic politicians.

Mass media during perestroika shifted from celebrating the African National Congress (ANC) — which the Soviet bloc, unlike its Western counterparts, had supported — to praising the apartheid government. Today, such a legacy accounts for liberal intellectuals’ reaction to this summer’s Black Lives Matter protests, which ranged from anti–anti-racism to open racism.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.