The Homecoming of Japanese Hostages from Iraq: Culturalism or Japan in America’s Embrace?

Marie Thorsten

http://japanfocus.org/-Marie-Thorsten/3157

In the spring of 2004, five Japanese civilians doing volunteer aid and media work in Iraq were kidnapped, threatened and released unharmed by Iraqi militant groups in two separate, overlapping incidents lasting just over one week. On their return to Japan (16 April 2004), the hostages appeared defensively solemn, having been harshly criticized and shamed for their effrontery to travel to a government-declared danger zone and undertake anti-war actions perceived as critical of both the Japanese and U.S. presence in Iraq. More than the abductions themselves, the inhospitable homecoming seized headlines around the world and marked one of the most searing images in Japan’s controversial involvement in the American-led war.

The first, more publicized, abduction was initially seen as a test of the commitment of Japan to support America, but within one week was transmogrified in Japanese media to public shaming of the victims. The five were compelled to say they were “sorry” for their transgression and were pressured to pay back some of their repatriation expenses to the state. In the story’s moral ending, they should have been acting with “self-responsibility” (jiko sekinin).

In 2004, still at the height of faith in global market fundamentalism, critics often spoke of “self-responsibility” pejoratively to question the pervasive rationale that individuals, more than governments, must rise to the challenges of economic uncertainty. In other circumstances this would be sensible, but “self-responsibility” in quotation marks negatively insinuates that governments are preoccupied with profits obtained in global markets, and have abandoned responsibility toward their own (unwealthy) citizens. Japan’s leaders seized the hostage homecoming to rearticulate jiko sekinin back into the embrace of cultural nationalism, but for critics of excessive governmental power, the term still retained its negative connotation.

Neoliberalism, also called market fundamentalism, conceptualizes winners and losers according to the laws of the marketplace. But it can also provide opportunities for individuals to take their interests, skills and citizenship outside their borders—which is exactly what the five persons did by asserting their freedom to work in Iraq independent of the government. But amid war, which heightens loyalties and exclusions, the individuals were redefined as subjects of a nation, even though the state, and many of their fellow citizens, did not reciprocate responsibility toward them: the five were harassed and ostracized, as if their citizenship was suspended.[1] This is characteristic of neoliberal regimes that actively produce “disposable others,” explains Takahashi Tetsuya, who reminds us that “responsibility” entails a relationship toward others. Instead, orthodox proponents of Japanese state policies were using the concept as “a rhetorical device to discard whoever [is] in the weaker position at any given moment.” After the repatriation, Takahashi adds, parents of the hostages were also charged with inadequate jiko sekinin, personal responsibility, in a “feudal sort of joint [parent-child] liability.”[2]

Many critics of the inhospitable homecoming, in Japan and abroad, also drew essential lines of distinctiveness by shaming Japan’s own shaming, implying that this could happen only in provincial Japan, not in cosmopolitan Europe or America. Japan is well known for isolating non-conformists within its culture while simultaneously being isolated in the international community. For Samuel Huntington, Japan is the “lonely state” that does not fit anywhere else in his taxonomy of clashing civilizations.[3]

Seen only as a strategic assertion of a unitary culturalism to define the nation, the jiko sekinin debacle distracted from recognition of the pressures other countries felt to be “responsible” to America to support the Iraq war. The last throes of support for the “with us or with the terrorists” binary logic in which the conflict began came to an end in the spring of 2004, the time of the two incidents. Within the same month of the Japanese homecoming, the Abu Ghraib prison abuses were starkly exposed to the world, helping to unravel American claims of moral superiority that had gone unchallenged in the nationalistic atmosphere permeating the early phase of the “war on terror.”

Were the hostile homecoming incidents more about the “responsibility” of nonconformists to Japan, or about the responsibility of Japan to America? In either case, the discourses those questions generated, that of cultural distinctiveness or alliance unity, belied the many gestures of cross-national community taking place throughout the ordeal, from capture to repatriation.

States of Exception, Alliances of Exceptionality

It would be easiest to explain the shaming of the hostages as the result of ancient traditions. But cultures are mutable, and politics of spectacle are often unstable and unpredictable.[4] Wars and political instability can invite arbitrary power, prompting the state itself to seize a kind of “self-responsibility” by unilaterally declaring that a “state of exception” exists. Giorgio Agamben writes that the state of exception occurs with a legitimate “standstill of the law,” when the rules and norms of a society are suspended but not eliminated; citizens lose rights, but not their bodies, in the course of being reduced to “bare life.”[5] Though an ancient concept, the state of exception became a dominant paradigm of the U.S. reaction to 9/11.[6]

In another era, de Tocqueville appraised self-exceptionalism as connected to America’s origins as a democratic nation-state, and to its roots as an exemplar of Puritanical Christianity.[7 ] The application of self-exceptionalism to foreign policy became conspicuous after the end of the Cold War, as the United States began to exempt itself from several international agreements concerning land mines, nuclear test bans, global warming, human rights, and the creation of an International Criminal Court.[8] Particularly after America invaded Iraq in March 2003–an act of aggression neither for self-defense, nor authorized by the United Nations– the question of American exceptionalism moved to the fore of global debates.[9]

In Japan, the discourse on unique “Japaneseness” (nihonjinron) becomes especially active during times of threat, such as during the Second World War and the economic “trade wars” of the 1980s. Japan’s culturalism is also cultivated through the external gaze, through non-Japanese analysts such as Huntington who sustain the representation of Japan as a resolutely peculiar nation.

Then-U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice also attempted to define temporal exceptionalism. In “extraordinary times,” such as World War II, the Cold War and 9/11, she explained, “the very terrain of history shifts beneath our feet and decades of human effort collapse into irrelevance.” Leaders must transform alliances to meet new purposes and “enduring values.”[10] The defeated Japan of 1945 was also a special model for the current U.S. occupation of Iraq, she wrote, recalling the favorite anecdote of President George W. Bush: that his father was shot down by the Japanese as a young pilot in World War II, but later proved as U.S. president that former war enemies can become friends.[11]

The two rhetorics of exceptionality meet in the discourse of the U.S.-Japan security alliance. Huntington not only called Japan a “lonely state”[12]; he also wrote that America is a “lonely superpower”[13], but together the two lonely hearts constitute a pillar of global power. America and Japan possess the world’s first- and fifth -largest defense budgets[14], and the first-and third -largest economies.[15] Since the 1980s, political and military leaders have institutionalized the incantation of the special relationship between the two nations, frequently quoting Ronald Reagan’s declaration, “Together, there is nothing our two countries cannot do,” or former Ambassador Mike Mansfield’s assertion that the two countries represent “the most important bilateral relationship (in the world) – bar none.”[16] The media invented affectionate variations, referring to the “Ron-Yasu relationship” (Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro and President Ronald Reagan) and the “George-Jun alliance” (Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro and President George W. Bush).

Koizumi, prime minister during the hostage incidents, is a self-described “die-hard pro-American,” and an Elvis and Hollywood fan whose invitations to Bush’s Texas ranch also served the American leader well. For reasons of history even more than the “personal chemistry between leaders,” according to The Weekly Standard, Bush considered Japan “a living rebuke to critics of his pro-democracy strategy in the Middle East.”[17]

The Iraq war, for many security officials in both Tokyo and Washington, provided the fortuitous opportunity for Japan to finally become a militarily “normal” nation, which also opens the window for joint exceptionality. While the U.S. put aside international conventions on warfare and the treatment of prisoners, Japan made exceptions to Article Nine of its Constitution, which mandates that the nation “forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes.” Japan has also made apparent exceptions to its Self-Defense Forces Law of 1954 which stipulates that ground, maritime and air forces (SDF) can maintain national security only by defending the nation against direct and indirect aggression, and it has made de facto exceptions to its “three non-nuclear principles” stating that the nation will not possess, produce or admit into the country any nuclear weapons. Announced in 1967, the non-nuclear principles were adopted by the Japanese parliament in 1971 and earned former Prime Minister Sato Eisaku the Nobel Peace Prize in 1974. But the naval base in Yokosuka now hosts the nuclear-powered carrier, the USS George Washington, an arrangement openly validated by leaders of both nations as if there is no contradiction.[18]

After 9/11, American officials pressed Japan to “show the Rising Sun” in Afghanistan, to “put boots on the ground” in Iraq, to “quit paying to see the game, and get down to the baseball diamond”.[19] In 2003, public opposition to the dispatch of the SDF to Samawah, Iraq, was around seventy to eighty percent, but by early 2004 a small majority was shown to favor dispatch after the troops had been sent.[20] Japan’s eventual contribution of 600 troops to the American occupation of Iraq may have constituted a symbolic peg in the “coalition of the willing.” But Japan and Okinawa have long served as a linchpin of American security efforts across Asia and the Pacific.

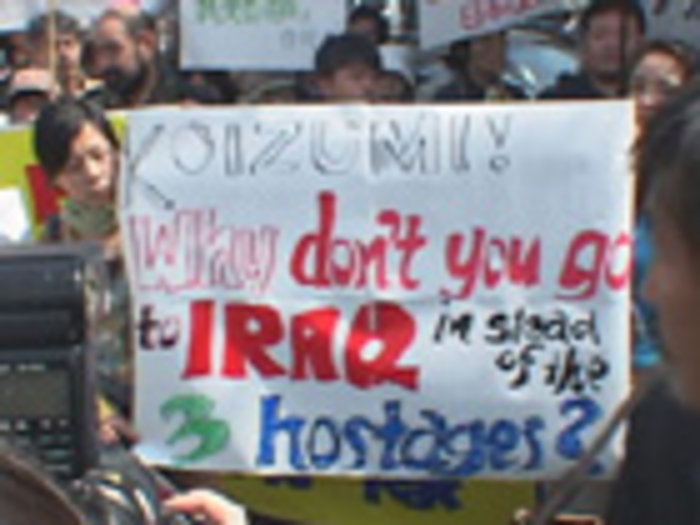

Anti-war protests in Tokyo on 9 April 2004 (source: AcTV)

The five Japanese taken hostage in Iraq were critical of the American-led invasion and Japan’s supporting role in the war. Their critics and harassers failed to see this as democratic behavior consistent with their Japanese citizenry. Moreover, for their political struggles independent of the Koizumi administration, their refusal to comply with restrictions on movement, and their concern with conveying a “truth” of the Iraq situation via the Internet and other media, the five Japanese citizens also exhibited a sort of democratic global citizenry as well. Failing to recognize the simultaneity of national belongingness and transborder democratic action, pundits reduced the incident to hostage shaming, led by key Japanese government officials reversing the charges of “responsibility” first aimed at them, and Japan-shaming, with analysts in both Japan and the U.S. criticizing Japan’s social insularism. Below is a review of these circumstances, focusing on the more widely reported first abduction.

The Hostage-Taking

The most conspicuous victim, Takato Nahoko, then 34 and an independent aid worker, had lived in Iraq previously and traveled back and forth from Japan primarily to fund a shelter for street children; she also assisted hospitals and was well-known to many of the aid workers in the area. Imai Noriaki, an aspiring journalist who was then only 18, traveled to Iraq only a month after graduating from high school. He had hoped to collect material for a book about children exposed to depleted uranium to contribute to a local social movement in Japan. Koriyama Shoichiro, then 32, entered Iraq as a freelance photojournalist determined to present an accurate account of Iraq otherwise unavailable to Japanese citizens. Though it was originally not widely publicized and perhaps not known to his captors, Koriyama was a former member of the SDF. The victims, and Takato in particular, were outraged by the American-led invasion of Iraq and critical of claims that Japan’s SDF activities, which were described by Japanese authorities as supporting the Iraqi people insisting instead that they merely supported the American occupation.[21] Takato was a former aid worker in India; Koriyama had just traveled from Palestine.

One week after Takato, Imai and Koriyama were abducted (7 April 2004), two other Japanese civilians, Watanabe Nobutaka, then 36, and Yasuda Jumpei, then 30, were taken captive in a separate incident (14 April) and released within three days. Watanabe, like Koriyama, was a former SDF member and at the time of the kidnapping a peace activist. Yasuda was working as a freelance photographer and was making his fourth trip to Iraq. Watanabe and Takato both had websites exposing conditions under the occupation, with summaries of local opinions they heard in Iraq particularly regarding the deployment of Japanese troops.[22] Though the five civilians have been collectively characterized as humanitarian or NGO workers, only Takato, Imai and Watanabe had ties to aid work of varying types and degrees, and the work of all five overlapped with their personal interests in gathering and disseminating information about the Iraq War, particularly Japan’s role in it and the impact on the Iraqi people.

The first group of three met at a hotel in Amman, Jordan, and agreed to take a taxi across the Iraqi border. When they were abducted at a petrol station on the Jordanian-Iraqi border in the early morning hours of 7 April, the humanitarians became typecast in their identities as Japanese nationals; the armed captors accused them of being spies for the Japanese government, and by implication the American government too.

The kidnapping of the Japanese, and soon, dozens of other international civilians by various militia groups, portended a reversal of the purported imminent American victory. It occurred just one week after the grisly murders, on 31 March 2004, of four American contractors whose bodies were dragged through the streets of Fallujah, hung on a bridge and beaten. The kidnappings of Japanese, Korean and other civilians not part of the original U.S.-UK-led assault on Baghdad furthered the perception that major hostilities, despite Bush’s “mission accomplished” declaration, were increasing rather than declining. Videotaped scenes of the captors holding guns and knives to the Japanese citizens’ necks and denouncing the invasion were shown widely across the world (and later featured in Michael Moore’s documentary film, Fahrenheit 9/11). In the video, the captors claimed they would execute the three civilians if Japan did not pull out its troops within three days.

Image from video showing hostages threatened with knives (AP photo)

The kidnapping tested the Japanese government’s resolve to defend its controversial dispatch of the SDF to Iraq as a humanitarian mission, pitched not as direct support for the U.S.-led occupation but as a broader gesture of support for the Iraqi people. During the first days of the crisis, many Japanese citizens demanded the pullout of the Self-Defense Forces in order to get the three civilians released; they wanted, then, what the kidnappers wanted. Family members of the victims made emotional pleas in several press conferences and collected 150,000 signatures on a petition urging the government to withdraw the troops.[23] Hundreds of civilians also protested the SDF deployment outside the prime minister’s residence and in other areas around Tokyo.

Family members submit petition to government (AP photo)

By the end of the ordeal, however, when the abductees were safely released, attention turned to one aspect of this constitutionally pacifist nation. Japan’s government officials charged that the trio had failed to exercise jiko sekinin, “self-responsibility,” by venturing out to government-decreed dangerous places for no compelling reason. Family members apologized to officials for “causing trouble” and having an “impolite attitude” toward the state. Although safely released, the victims returned to Japan downcast and silenced, as if criminals, issuing only statements of apology for the trouble and financial burden they caused to tax-paying compatriots; they agreed to repay some of the expenses incurred.[24] Some were plagued with threatening phone calls and other forms of harassment, instilling depression and post-traumatic syndrome.

This shaming and silencing was not the only way the kidnapping victims were “brought home” to their Japanese national identities. The statements below from international sources also relied on stereotypes to lend authority to their critiques.

The Los Angeles Times columnist Tom Plate wrote off the event as another round of “Asian values” that Westerners will never understand. According to Plate, the Japanese media had “downplayed” the story, in comparison to the “psychodrama” that would have unfolded had it occurred in America (referring to the hostage-taking itself, not the homecoming). Plate then deployed the oldest East-West stereotypes,

That’s because the West nurtures a culture of individualism and entrepreneurism. That’s especially evident in our aggressive journalism (heroic correspondents “getting the story” against all danger) and in the rise of our civil-society nonprofits. In Japan, by contrast, the news media tend to react more as a group (or not overreact as a group), and the civil-society nonprofit sector is in relative infancy.

One reason for the difference between East and West is that the former’s culture still has the capacity to reflect hierarchical values: In effect, father (the authority figure) knows best. And so when father is government, and the government strongly advises its people not to go to Iraq, and people go anyhow, then it’s their fault and their problem.[25]

New York Times Asia correspondent Norimitsu Onishi similarly drew attention to the Japanese peculiarity of o-kami, an anciently conditioned obeisance to god-like officials.[26] Then-Secretary of State Colin Powell, in a widely televised interview with Japan’s TBS network, paternalistically advised,

The Japanese people should be very proud that they have citizens like this. . . and the soldiers that you are sending to Iraq that they are willing to take that risk. . . But, even when, because of that, they get captured, it doesn’t mean we can say, “Well, you took the risk. It’s your fault.” No, we still have an obligation to do everything we can to recover them safely.[27]

Such reports generally fell back on dichotomies between “Japan” as an exceptional, insular country and America and others as part of a more integrated and sophisticated global society. Powell’s widely quoted statement and others like it overlooked the fact that the hostages and their family members had made strongly political, anti-Bush, anti-SDF-deployment statements, which American aid workers, despite their generally greater numbers and longer experience, were reluctant to publicize in the early phase of the war.

Bashing

Kobayashi Masahiro’s Bashing premiered at the Cannes International Film Festival in May 2005 and offered one of the most scathing criticisms of the incident.[28] In the prosaically minimalist film, a young woman named Takai Yuko (Urabe Fusako) experiences derision, hostility and ostracism in her unsociable, provincial seaside community. Crank calls to the family’s Spartan working-class apartment reveal that Yuko has been doing aid work in an unnamed Middle Eastern country; the anonymous voices sneer at her selfishness, her failure to act with self-responsibility and her lack of concern for her countrymen, all of whom are said to hate her. It does not take viewers long to realize that this is a “fictional” portrayal of Takato Nahoko, who is also from Hokkaido (where the film is set).

Kobayashi’s film Bashing (source: Cinebel)

Yuko’s physiognomy conveys the stages of depression with an honesty lacking in Hollywood histrionics. At one point a solitary tear roosts defiantly on the tip of her nose, creating a witchy elongation that might be satirizing her homecoming, or else, like the ocean she frequently gazes into, pointing her in a direction elsewhere.

“Elsewhere” is the only refuge in the film—either the temporal “elsewhere” of the stepmother who urges a “this too shall pass” waiting period, or the geographic “elsewhere” Yuko has just returned from. When her last tie to her hometown has been lost, she makes a flight reservation to leave Japan forever.

The loneliness the viewer experiences is not just empathy with Yuko’s suffering from the bashing, but also the total lack of connective space between the protagonist and others. Yuko’s provincial world evokes Agamben’s “bare life” and is far more desolately conformist than that of Takato Nahoko, who experienced bashing but also enjoyed support, mobility and communication denied to Yuko. Even Yuko’s computer has frozen and she has thrown the telephone out the window. In his “Director’s Notes,” Kobayashi states that the “fiction” he presents could be about Takato, or it could be universal, a story that involves you and me. And yet try as it may, Bashing failed somehow to transcend its reference to the experiences of Takato and the other abductees in 2004.

After its premiere in Cannes, Kobayashi remarked that the foreign reporters were very interested in knowing how to separate the real situation in Japan from the director’s fictionalization. They also wanted to know why such a thing could happen in Japan, and he replied that he did not have a good answer.

Though the cultural self-caricature is intended to be critical, Kobayashi has recreated the same assumptions of nihonjinron in its worst form of a pure cultural self: monolithic, unchanging, prone to blindly following the slogans of the leader and, indeed, frozen in time and physical geography as “sakoku,” Japan’s isolation policy during the feudal era. “Do you think Japan has changed in the year and a half since the kidnapping of Takato and the others?” I asked him, during his presentation following the film’s showing at Doshisha University in the fall of 2005. He responded that the tendency toward bashing noted in the film has since transformed into apathy, and the most likely response of Japanese to his film’s message would be to ignore it. Then he added, most likely in obligatory response to my very gaijin appearance in the audience, that Japan, after all, is a mura shakai (village society), tsumaranai (insignificant) and it will not change (Nihon wa kawaranai).

It has always been disconcerting that such utterances of Japaneseness from Japanese seem to echo the very statements used by Americans during the Pacific War to create racial otherness. American propaganda of that era used such egregiously racist stereotyping as, “A Jap is a Jap is a Jap” (writings of General John DeWitt)[29], or Frank Capra’s infamous saying in his 1945 documentary,Know Your Enemy: Japan, that the Japanese were like “photographic prints off the same negative.”[30] Dower has called such a tendency “collusive Orientalism”: Japanese invoke their own stereotyping because in doing so they simultaneously promote the myth of uniqueness or national unity.[31] There is still a fine line between portraying the myth of fatalistic uniqueness because one firmly believes in it, and portraying the myth to censure it while still feeling that it will never change. (In fact, Kobayashi was also bashed for making the film as it circulated in Japan.)

Beyond Culturalism

Of course, there was a Japaneseness about this ordeal as the hostages were made to apologize, bow deeply and reflect on the troubles they caused. The homecoming spectacle drew attention to the ostracism of Japan’s own citizens being treated as excluded outsiders despite having carried out international aid, research and reportage in a danger zone. But conflict within supposedly conformist Japan ensued. And the nuances in this event, beyond those observed in the distinction between the cultural twain of East and West that shall never meet, are more compelling when thinking about how wars generate moral panic in many societies. One can find instability beyond the unifying codes of nation-states in the following examples.

The “graphic” videotape: The first global exposure of the three hostages was through the videotape delivered to Al-Jazeera and the Associated Press Television News. Against a background of bullet holes, the blindfolded, kneeling trio were fuzzily seen vocalizing their terror while masked men hold guns and knives to their necks. The captors identify themselves as the Saraya al-Mujahideen and issue the statement, “We tell you that three of your children have fallen prisoner in our hands and we give you two options—withdraw your forces from our country and go home or we will burn them alive and feed them to the fighters.”[32] By now this kind of hostage-taking video has become all too familiar in the Iraq conflict; this particular video, however, stands out for its dramatic elements. It was often described in the press as “graphic,” and it made this case the most conspicuous of the wave of abductions that occurred around the same time in Iraq (including seven South Koreans, one Briton, one Canadian, two Israelis and, a few days later, two more Japanese taken by different brigades).[33] What is conveyed in such a message is that the three citizens have become unwitting representatives of the Japanese state, and the Japanese state—even for all its rhetorical gestures to identify itself in a humanitarian capacity and not as an official member of the “coalition of the willing”—becomes just that, an aid to the American invasion and occupation.

In reverse, the implication that the captors likewise represented a unified Iraq, was also present—but belied by the fact that, at the time at least, the various abducting groups were likely to be disparate. The Japanese trio revealed after their release the extent to which their own captors were divided. What made their situation unnerving was not just that they were held captive, and believed they would lose their lives, but also that they were held in several different places, and were passed from captor to captor and given very different receptions. At times they were bound and bullied and treated with hostility, suspicion and threats. At other times they were shown family photos, served home-cooked meals, apologized to, and politely bid farewell.

As revealed in Takato Nahoko’s memoir of the captivity, one faction of kidnappers spent some time accusing them of being spies. Having the most experience in Iraq, Takato passionately defended her humanitarian work to help transport medical supplies and provide shelter for homeless children. She provided names of Iraqis who could verify her identity and character. The captors then left and returned with tobacco and food. Yet just as the conversation was turning to the tastiness of noodles and vegetables, someone came in with a hand-held video camera. The interpreter turned to the trio and repeated several times (quoting from Takato’s recollection): “Your life will be guaranteed. But in return, this is bad but, would you please cry for us?”[34]

Takato’s memoir (source: Amazon.jp)

The three were then blindfolded and forced to kneel down on a floor. The 18-year-old Imai was apparently kicked several times, and was urged to cry out his pain (“it-te-e” in rough Japanese) while all three captives and their captors chanted, “No Koizumi,” and knives were held to the victims” throats. The blindfolds were removed and the interpreter asked again, “This is bad, but would you cry for us now?” One captor moved his sword toward Imai and the captors shouted in English, “Cry, cry!” – moving at least Takato to actual tears. Koriyama (the journalist) asked if she was all right; then the interpreter also told her she could stop crying. Finally the captors themselves said in English, “Sorry, sorry,” and one leaned over and kissed her on the head, reminding her of the rambunctious street children she worked with.[38] (The gist of this account was confirmed in press conferences with the other two victims.)

After their video performance, the captives were again blindfolded, put in a car and moved around again several times until their release. According to Takato’s memoir, it may have been the bombing around the area (especially Fallujah) putting them in danger, as well as disagreement among captors over their fate, that caused the peregrinations. In any case, none of the victims had any idea that the video with the contrived emotions was attached to a statement issuing their death threats and urging the pullout of the SDF.

After their release through intervention by the Islamic Clerics Association, Japan’sAsahi Shimbun editorialized, “In Iraqi society as a whole, the armed bands that snatch foreigners are but a tiny minority. We feel, however, that one of the factors contributing to the hostage-takings is the tacit approval that many give such acts amid growing anti-American sentiment. What really worries us is that such Iraqis have started to think the SDF came to Iraq to cooperate in the U.S. military’s occupation.”[36]

Takato and Imai on Al Jazeera after their release (AP photo)

Bureaucrats and blogs: Immediately following the news of the abduction, Foreign Minister Kawaguchi Yoriko issued her own video statement to the abductors in which she confirmed the innocence of the three citizens and the commitment, and financial generosity, of Japan to the humanitarian reconstruction of Iraq,

The three Japanese are private individuals, and friends of Iraq. . . The People of Japan has (sic) both respect and friendship for the people of Iraq. For many years, Japan has actively cooperated for building hospitals and schools. Even as I speak Japan is working for the reconstruction of Iraq, with a significant sum of money and personnel. Japan’s Self-Defense Forces are also dispatched for this purpose.[37]

After releasing her video, Kawaguchi held telephone talks with the Syrian government and received assurances of their cooperation in the release of the three citizens.

Except for affirming that he would not give in to the abductors’ demands by withdrawing the troops, Prime Minister Koizumi, however, was noticeably inconspicuous; he was preparing to meet with U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney who arrived the day after the abduction (April 10). Cheney was planning to stay four days in Japan, to join in Japan’s lineup of commemorative activities surrounding the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Japan-U.S. Treaty of Peace and Amity (Treaty of Kanagawa) on 31 March 1854. The festivities would offer Cheney the opportunity to express appreciation to Japan for providing troops and engineers in Iraq. Specifically, his agenda included asking Japan to double its noncombat forces in Iraq.[38]

While the mass media had long been planning to fete U.S.-Japan amity, what they got instead, in the immediate start of the hostage crisis, was a test of the U.S.-Japan alliance, a reality that was antithetical to the public rhetoric of binational unity that the festivities were to promote. On 31 March 2004 in Washington, D.C.—the same day that Iraqi grenades killed four American civilian contractors and a mob hung two of them from a bridge over the Euphrates—150 American dignitaries, including members of the Pentagon, the State Department, Congress and the corporate community, joined Japanese dignitaries and descendants of Commodore Matthew C. Perry, the man credited with the Treaty of Kanagawa that opened Japan to the world after its long period of isolation, to celebrate peaceful U.S.-Japan relations. The ceremonies involved presenting a facsimile of the original treaty (burned long ago in a fire), showcasing an exhibit celebrating the treaty (organized by the National Archives), and making an addition to the celebrated line of cherry trees presented as a gift from Japan in 1912. In his remarks, Ambassador Kato Ryozo stated that “over those 150 years [of U.S.-Japan amity], our two worlds have merged into one.” The ambassador went on to praise the efforts of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces to aid Bush’s war on terrorism in the Indian Ocean and Iraq, and asserted that “[N]ever has the Japan-U.S. relationship been so close, and never has there been a time when it’s required that we be so close.” The American speakers also uttered the same words of selective memory, alliance unity and praise for Japanese assistance to the Bush administration’s antiterrorism efforts.[39]

In his widely-circulated essay, the American ambassador to Japan, Howard Baker, pitched the alliance as “the best team,”

We increasingly eat the same food, listen to the same music, and wear the same fashions. More importantly, we enjoy the same freedoms, and share the same values. As we see symbolized with Hideki Matsui playing here in Japan this month wearing a New York Yankee uniform, we are on the same team. As teammates, we work together for a common purpose, especially when the game is on the line.[40]

In Japan, the discourse of alliance unity was quashed amid the ensuing turmoil in Iraq, since after the abductions of the first three Japanese citizens only a few days after the Washington side of the amity celebration, the press homed in on the question of whether or not the Japanese public would in fact continue to support the troops. Broadcast and print media gave blanket coverage to the hostage-taking, alternating between the video footage of the hostages and the gathering of outspoken family members in Tokyo willing to take on Koizumi for his unflinching support of Bush and the American invasion.

On 9 April, family members urged Koizumi to withdraw the troops and not send in an American-led rescue team; they also grimaced at Foreign Minister Kawaguchi’s mention of the Self-Defense Forces’ humanitarianism and Koizumi’s referring to the hostage-takers as “terrorists,” fearing such statements would stiffen the resolve of the kidnappers. And family members charged Koizumi with his “personal responsibility” in a press conference in Nagata-cho (the government area of Tokyo). Though Koizumi did not meet with the seven relatives directly, he issued a statement saying, “This is not a problem concerning myself. This is a problem concerning how the whole country should cope with stabilization and reconstruction of Iraq.” The elder brother of hostage Imai replied, “That (comment) is unforgivable, considering our current sentiment.” The mother of hostage Koriyama replied, “I really feel that (in Koizumi’s view) the state comes before human rights of the three now confined.”[41] Family members also made other television and public appearances, and some spoke to Al-Arabiya, based in the United Arab Emirates, and to Qatar-based Al-Jazeera.

On whether the Japanese public supported Koizumi’s affirmation to stay the course, a Kyodo News telephone poll found that 45.2 percent disagreed with the decision, and 43.5 percent supported the policy to keep the troops in Iraq. The poll also showed that 80 percent felt Koizumi would be “responsible” if a Japanese were injured in Iraq, and 36 percent felt he should resign if a Japanese were killed there.[42] Fukushima Mizuho, leader of the Social Democratic Party, called on Koizumi to resign over his “responsibility” for the crisis, and demanded immediate withdrawal of Japanese troops from Iraq (10 April).

In 1960, massive mob protests against the U.S.-Japan security treaty were so strong that Japan had to stop President Eisenhower from making a state visit—the Japanese government having failed to meet American demands to keep the “leftists” under control. Demonstrations in 2004 in no way approached that level, but the Iraq war brought out political sentiments, both pro-Alliance/patriotic and anti-war (rarely, if ever, anti-American), that had been unseen in Japan for decades. Yet Koizumi’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) wasted no time throwing the discourse of “responsibility” back to the people. The following summary (mostly compiled by the Asahi Shimbun) presents key statements of government officials to blame the hostages and their families themselves as bearing “self-responsibility,”

9 April, from Environmental Minister Koike Yuriko: “Wasn’t that reckless? It is mostly their own responsibility to go to places deemed dangerous.”

12 April, from Vice Foreign Minister Takeuchi Yukio: “They must be aware of the principle of personal responsibility and reconsider how they can protect themselves.”

15 April, from Chief Cabinet Secretary Fukuda Yasuo: “They may have gone on their own but they must consider how many people they caused trouble to because of their action.”

16 April, New Komeito [an LDP coalition party] Secretary-General Fuyushiba Tetsuzo: “The government should reveal to the public how much it cost to respond to this crisis.”

16 April, Inoue Kiichi, minister in charge of disaster management: “The families should have first said they were sorry for causing trouble; was it appropriate for them to ask for SDF withdrawal first of all?”

27 April, Kashimura Takeaki, Upper House Member of Parliament: “I cannot help feeling discomfort in or strongly against spending several billion yen of taxpayers’ money on such antigovernment, anti-Japan elements.”[43]

Under pressure, the family members issued a series of apologies to the Japanese public beginning on 12 April. When the release of the trio was announced and confirmed, Takato’s brother and some other Japanese officials traveled to Kuwait to meet them. The gesture was not just meant to be friendly; the kidnapping victims needed to know about the atmosphere in Japan and that they would be expected to apologize. In Takato’s case it was already too late: she had already issued a statement claiming she bore no ill feelings toward the Iraqi people and hoped to stay there; Imai also stated he hoped to stay on (in fact he had only just arrived when abducted).

Over the next month, interviews and blogs latched onto the “blame the victim” mentality. Predictably, reporters dished dirt by showing that Takato was a former juvenile delinquent who sniffed paint thinner, that Imai’s parents were Communists and were exploiting the naïve young man for their own politics, and that ex-SDF member Koriyama was married once and divorced, with children. The tabloid Shukan Shincho delivered perhaps the most thorough censure of the hostages, reporting that the international terrorism department of Japan’s Police Agency first analyzed the possibility that the entire kidnapping was a hoax; many blogs argued it was. The tabloid also quoted a senior LDP source as confirming that a Japan Communist Party Youth League member was present at every press conference given by the families.[44]

The release statement: Another under-scrutinized piece of information was the release statement, loosely translated on 11 April by Kyodo News.[45] The statement sent by the militant group Saraya al-Mujahideen (Mujahideen Brigades) to the Arabic news channel Al-Jazeera revealed the “common ground” between the victims and the captors,

• It [the Saraya al-Mujahideen] wants the friendly Japanese public, who are still suffering from the abuse by the United States, to pressure the Japanese government to withdraw its Self-Defense Forces troops from Iraq because the dispatch is illegal and contributes to the U.S. occupation.

• It has decided on the release to show the whole world that the resistance in Iraq does not target peaceful foreign civilians of whatever religion, race, political party or rank.

• It has confirmed through its own sources that the (three) Japanese have been helping Iraqi people and that they have not been contaminated by subservience to the occupying nations.

• It made the decision also out of consideration for the pain of the hostages’ families and out of respect for the Japanese public’s stance on the issue. . . .

• It has heard the Japanese public say the U.S., which killed masses in Hiroshima and Nagasaki with atomic bombs, is carrying out a massacre in Fallujah using bombs banned internationally.

• It is committed to the holy war until victory. [46]

The gist of this partially translated statement linked the Japanese people to the Iraqi people because both were still suffering from American aggression, occupation and continued military subordination: specifically, Fallujah is mentioned as a counterpart to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This release statement was announced at a slow news moment, Saturday night, and was read again on Sunday talk shows the following day, but was rarely mentioned in major media after that. But on the famously congested “2 Channel,” an Internet bulletin board, detractors wrote that the abductors should not invoke “Hiroshima, Nagasaki” since those places were special to Japan only and the captors had no idea about their significance. [47] While there is no forgiveness implied here toward the criminal brutality of the abductors, the “Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Fallujah” reference did resonate with other anti-war citizens interested in relations with more peaceful Iraqis, and further weakens the illusion of national conformity within Japan.

With the sudden crescendo of “self-responsibility” diverting media attention from America’s war in Iraq to social wars in Japan, the Cheney visit was rendered unproblematic; the American vice president expressed his concern about the hostages, his appreciation for the SDF deployment, and his approval to Koizumi for keeping the troops in Iraq. On 13 April, just after the flames of “self responsibility” flared, Cheney gave a barely-publicized speech in Tokyo to honor the Kanagawa Treaty, calling U.S.-Japan relations “one of the great achievements in modern history.”[48]

Some of Koizumi’s critics doubted whether the Japanese government’s efforts led to the release of the hostages, as implied in the demand that the hostages pay the taxpayers back. Journalist Tachibana Takashi reported that Japanese officials were consistently one or more steps behind efforts undertaken by Iraqi citizens who became sympathetic to the hostages (and especially to Takato, who had worked for the Iraqi people) and were critical of the American occupation and Japanese troop dispatch. “Fundamentally the one who saved Takato was Takato herself.”[49]

Though the hostages and their families were silenced for several weeks, others critical of Koizumi continued to speak. On 26 April, more than sixty nongovernmental organizations urged officials and the media to stop blaming the victims personally, complaining that this in effect constituted an attack on all other aid workers and journalists in Iraq. In a joint statement signed by 3,000 individuals, the group asserted, “The notion of self-responsibility will create a misguided public sentiment that NGO members working in conflict areas are themselves responsible, even if their lives are threatened . . . and could lead to restricting NGO activities abroad.”[50] Moreover, although the victims were inundated with hate mail after their repatriation, Takato noted after publishing her memoir half a year later that she received letters of support as well as apologies for the hate mail after some time had passed and people understood the situation better.

The second pair of hostages, Watanabe and Yasuda, was actually more strident in their criticism of the media and government officials who were blaming the victims and their families for the abductions. Responding to the charge that they were “anti-Japan elements,” Watanabe responded dryly in a press conference soon after their release, “Yes, I am against Japan and thank you for recognizing my opinions.”[51] In June, Yasuda gave candid interviews revealing that he and Watanabe, like the first three, were treated differently by rotating captors and that he (Yasuda) even arm-wrestled with the children and taught them karate. “Half of me was happy I survived,” he stated; yet “the other half wanted to spend more time with them. I wanted to see more of their lives. I wanted to see them attack the Americans. I asked them to take me with them.”[52]

Not in America?

If journalists paid too much attention to Japan’s homogeneity, they paid insufficient attention to conformity in America. Reconsider Plate’s above-mentioned assumption that the cold hostage homecoming could only happen in the “East,” with its hierarchical values and obedience to the paternal sovereign, and its lack of heroic journalists and civil society enjoyed by the “West.” The media watch group, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), has compiled considerable evidence to show that, from 2002 until Bush’s “Mission Accomplished” putative “end of major hostilities” announcement in May,2003, America’s mainstream media repeatedly followed the “paternal sovereign” by failing to question the Bush administration’s claims of weapons of mass destruction, its main rationale for the invasion. Major news media gave short shrift to the writers trying to expose the faulty logic of the war while putting cheerleaders in the spotlight.[53] MSNBC’s Chris Matthews even gushed that,

We’re proud of our president. Americans love having a guy as president, a guy who has a little swagger, who’s physical, who’s not a complicated guy like Clinton … They want a guy who’s president. Women like a guy who’s president. Check it out. The women like this war. I think we like having a hero as our president. It’s simple.[54]

America and Britain also expected that journalists be “embedded” rather than “unilateral” in the early phase of the war. American leaders of the current Iraqi campaign invented the concept of “embedding” to refer to journalists who would be civilian members of military divisions and perhaps even train with the soldiers. Embeds theoretically have better access to military information and better opportunities to report on and photograph the war; perhaps the biggest bonus is that they get military protection and can feel safer. The trade-off, critics point out, is that embeds become less critical. A Newsweek story quoted an embed who said that any embedded journalist who didn’t feel conflicted about the thought of being pressured to write flattering stories for the government was a liar.[55]

Warnings to the non-embedded, so-called “unilateral” journalists echoed Japan’s admonitions to the self-responsible: authorities announce that it’s too risky to be on one’s own.[56] “Risky” may be an understatement: Reporters Without Borders reported that 225 journalists and media assistants have been killed in Iraq since fighting began there in March 2003, making that conflict the bloodiest for journalists since World War II.[57]

Several months into the war, a few embedded reporters demonstrated their courage to write stories inconsistent with official military spin. Instead, writes Kellner, it was the U.S. broadcast networks that were “on the whole more embedded in the Pentagon and the Bush administration than the reporters and print journalists were in the field.” The television stations produced “highly sanitized views of the war, rarely showing Iraqi casualties,” and profited as “cheerleaders for the country’s war effort.”[58]

Media diversions are common in war; the repetitions of “freedom,” “democracy” and “humanitarian action” distract from or even silence reportage on catastrophic failures and human tragedy.[59] Japan’s moral affirmation of jiko sekinin distracted from Japanese anti-war protests, cracks in the 150-year amity between the United States and Japan, and the symbolism of the equation of Fallujah with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. America’s mass conformity at the start of the war in 2003 used heroics to distract from the illegal invasion. Kellner describes the “Jessica Lynch story” as a Pentagon-produced mythology fed into broadcast networks. Lynch was an attractive young POW for whom American troops supposedly staged a dramatic rescue, hyping the story (it was later discovered) not only to rally mass support for the U.S. troops, but also to distract media from telling the real story, which was the beginning phase of the coalition’s entry into Baghdad.[60]

Finally, the initial disclosures of prisoner abuse in the Abu Ghraib facility in Iraq were exposed on 28 April 2004. Visual evidence of naked and hooded prisoners, placed in bizarre, stressful, painful, scatological, and sexually humiliating positions, generated protest and censure throughout the world. The exposure occurred less than one month after the Japanese hostage incident, and the Bush administration also made efforts to pin “responsibility” for the abuse to a small group of outsiders, in this case, the “bad apples” playing “Animal House on the night shift.”[61] Such damage-controlling phrases showing the “deviance” of the Abu Ghraib prison guards attempted to distract the public from the officially sanctioned torture used throughout America’s overseas prison network. According to journalism professor Mark Danner, the majority of Americans was willing to believe the myth of “bad apples” just so that their faith in the American military project would not be disturbed.[62]

The Abu Ghraib photos not only opened up wider investigations into communication along a military chain of command, they also led to more critical uses of media to educate Americans about abuses of authority during war.[63] Independent media in particular have created more and more spaces for critical voices to express opposition to the unconstitutionality of the wars and associated interrogation and incarceration practices. Even in mainstream media, these topics have come to be debated almost daily, and former Bush officials, former interrogators, and former military personnel in the capacities of “winter soldiers” or resistors have also begun to air their stories.

The five former abductees continued their work after a brief hiatus of hiding from public scrutiny. They have written memoirs and made several presentations in Japan and abroad. Takato has continued her work for Iraqi schools and hospitals through several NGOs, and in particular, through her own Iraq Hope Network.[64] According to her blog, she made a brief trip back to Iraq in April 2009, in part to put the experience of five years ago behind her.[65]

At least two incidents offered a chance to compare American reactions to a hostage situation similar to that of Japan’s, though both occurred after the Iraq war’s first year of intense media-supported nationalism. In November 2005, four male members of the Christian Peacemaker Teams (CPT) were kidnapped in Iraq. One was American; two were Canadian, and one was a British member of the organization that is supported by international pacifist churches such as Mennonites and Friends, and also includes non-Christians. The group practices non-violent, non-proselytizing activism, and in Iraq had begun to document prisoner detainee abuses committed by Americans even before the Abu Ghraib disclosure. Ignoring their faith-based service, conservative radio host, Rush Limbaugh, first raised the possibility that the kidnapping might be a hoax. He then declared that he “liked” the kidnapping, or “any time a bunch of leftist feel-good hand-wringers are shown reality.” [66] Tragically, the American member was killed, and the other three released after three months.

The second incident was the kidnapping of the American journalist Jill Carroll in Iraq in January 2006. Nearly two years since the abductions of the Japanese citizens, many things had changed. Hostage-taking had become more commonplace and dangerous, and domestic and international support for the American-led war had already declined. Jill Carroll was released safely after 83 days rather than one week, and although she was a free-lance journalist, she was then on assignment with the Christian Science Monitor to interview a top Sunni Arab political leader. Still, there were important similarities. Like Takato, Carroll had studied Arabic and made many efforts to interact on friendly terms with Iraqis. While in captivity, she made statements, always appearing in hijab, critical of Bush’s “illegal war” in Iraq. Just as private efforts were made to advocate for the release of the Japanese hostages, especially owing to Takato’s network of humanitarian workers,[67] Carroll’s employer, the Christian Science Monitor, according to veteran journalist Robert Zelnick, also made every effort to gain international support for her release, mobilizing a long list of individuals and organizations that included Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, America’s Council for Islamic-American Relations and Iraq’s Muslim Scholars Association.[68] Upon being freed, she stated while still in Iraq, her captors treated her well, though she had been moved around frequently and never knew what would happen.[69]

Echoing the backlash against the Japanese hostages in Japan, angry citizens in America also charged that Carroll had unwisely exposed herself to danger; that she had become one of the terrorists herself; and that she was an anti-American traitor. Most rants rumbled from the blogosphere [70], but some were urged on by professional commentators, including one who compared her to a “Taliban Johnny” who “may be carrying Habib’s baby.”[71]

Unlike the Japanese victims, when Carroll left Iraq she quickly recanted the statements she had made there as propaganda she was forced to do under threats to her life. Yet bashing against her continued, even though her abduction and release occurred after American media had become much less conformist in their support the war. The point is that demanding conformity of one’s own citizens has also occurred in America in times of heightened nationalism and compromised democracy; though America celebrates its relative free speech, tactics echoing McCarthyist red-baiting during the Cold War are not entirely in the past.

Conclusion

As for whether the Japanese hostage homecoming can be understood as an expression of Japanese cultural norms demanding obedience to the group, or geopolitical norms demanding Japanese subservience to America by keeping dissidence under control, the answer is both, and more. Beyond the myths of unchanging cultural norms, the security regimes of nations at war invariably generate increased demand for socio-political conformity, and in the case of America and Japan, the symbiosis of national feelings of unity also helps maintain the exceptionality of the U.S.-Japan alliance. Until the decline of Americans’ own support for the Iraqi invasion—during the window of grace between “Mission Accomplished” and Abu Ghraib—insufficient attention was paid to anti-war pressures within American society and to opposition in Japan to that nation’s support for the war and the alliance. [72]

Not only is it necessary to rethink social relations beyond nations, it is also important to recognize the democratic potential of media “common places” that give voice to a diverse citizenry within and beyond borders, preventing manipulative tactics such as changing the meaning of “self-responsibility” to “nationalist conformity.”[73] In both Japan and America, journalists and aid workers hoping to put checks and balances on abusive powers of nations were rebuffed in the early phase of the Iraq war. But such media diversity is necessary to challenge emotional reactions that coalesce around tired and uncomplicated images of nations, a reaction that in itself can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Marie Thorsten is an Associate Professor in the Social Studies Faculty of Doshisha University, where she researches and teaches courses on U.S.-Japan Relations, Cultural Studies and Global Education. She expresses her gratitude to Professors David Campbell, Jeremy Eades, Eyal Ben-Ari, and Asia-Pacific Journal reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. She wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Marie Thorsten, “The Homecoming of Japanese Hostages from Iraq: Culturalism or Japan in Amerca’s Embrace?” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 22-4-09, June 1, 2009.

Notes

[1] See Aihwa Ong, Neoliberalism as Exception: Mutations in Citizenship and Sovereignty (Duke University Press, 2006), 5.

[2] Takahashi Tetsuya, “Philosophy as Activism in Neo-liberal, Neo-nationalist Japan” (interview), Japan Focus, November 3, 2007 (orig., 2004-2005, trans. Norma Field), 8.

[3] Samuel P. Huntington, “Japan’s Role in Global Politics,” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 1(2001), 139.

[4] Douglas Kellner, Media Spectacle and the Crisis of Democracy (Boulder: Paradigm, 2005), 78.

[5] Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception (trans., Kevin Atell) (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 50, 84-85.

[6] Agamben, State of Exception, 2-3.

[7] See Peter J. Spiro, “The New Sovereigntists: American Exceptionalism and Its False Prophets,” Foreign Affairs (November/December 2000): 9-15.

[8] Frequently cited rejected treaties include the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty; the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction; a protocol to create a compliance regime for the Biological Weapons Convention; the Kyoto Protocol on global warming, and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. The United States has also signed but not ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women. When President George W. Bush took office, he ‘unsigned’ the United States from The Treaty Establishing and International Criminal Court, which had previously been signed, but not ratified, by President Clinton. See Isaac Baker, “Rogue State? US Spurns Treaty after Treaty,” Inter Press Service, 8 December 2005.

[9] For further information on perception of the Iraq War as illegal, see David Krieger, “The War on Iraq as Illegal and Illegitimate,” in Ramesh Thakur and Waheguru Pal Singh Sidhu, eds., The Iraq Crisis and World Order: Structural, Institutional and Normative Changes (New York: United Nations University Press), pp. 381-396.

[10] Condoleezza Rice, “Princeton University’s Celebration of the 75th Anniversary Of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs,” lecture presentation, Princeton University, September 30, 2005 (U.S. Department of State).

[11] The comparison between the Allied Occupation of Japan in 1945 that enjoyed the full support of the international community, and Iraq in the early moment of the invasion, was so dangerously flawed, according to historian John Dower, that it should have instead “stood as a warning that we were lurching toward war with no idea of what we were really getting into.” See John W. Dower, “A Warning from History,” Boston Review (February/March 2003).

[12] Samuel P. Huntington 2001, ibid.

[13] Samuel P. Huntington, “The Lonely Superpower,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 1999: 35-49.

[14] Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “Recent Trends in Military Expenditure.”

[15] CIA World Factbook, 2008 estimates of GDP (purchasing power parity).

[16] Inoguchi Takashi, “America and Japan: The Personal is Political,” Open Democracy, 17 June 2004, 1-6, retrieved at www.opendemocracy.net on 20 August 2006.

[17] Duncan Currie, “The Other Special Relationship,” The Weekly Standard, 20 December 2004, 16.

[18] See Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Record of Discussion.”

[19] Cited in Gavan McCormack, “Koizumi’s Japan in Bush’s World: After 9/11,”Japan Focus, 12 October 2004; 2-3.

[20] Cited in McCormack 2004, ibid., 9. Also, Japan pulled its troops out of Iraq in 2008 and is attempting to ease the burden of American militarism on Okinawa, but other plans show the alliance is being redefined and expanded even more along military lines. A new realignment package will have Japan and America placing their command centers on the same bases in newly defined “base towns” throughout the country, and Japan has agreed to pay 700 billion yen to help the US set up a new base in Guam. (“Japan-U.S. Relations” [editorial], Asahi Shimbun 4 May 2006, 28.) In 2004 the United States and Japan agreed to exchange information on the deployment and operations of a missile defense shield.

[21] Koizumi’s ability to steer public and official opinion toward support of the troops had much to do with his linking their mission only to that of humanitarian, non-combat, reconstruction; he also assured the public “there is no security problem” in Samawah—a point later qualified into rendering Samawah as not having any hostilities conducted by “states or quasi-state organizations.” The relatively secure, isolated situation for the Japanese soldiers was also described as operating under joint command headquarters, rather than America’s requirement of “unified command.” Cited in McCormack, ibid., 2004, 5-7.

[22] See Tachibana Takashi, “Koizumi Iraq hahei ‘kurutta shinario’” (The “desperate scenario” of Koizumi’s Iraq dispatch) Gekkan Gendai [monthly Gendai] 38, no. 6 (June 2004): 28-41.

[23] “Former Japanese Iraq Hostages Criticize Media, Govt.,” Reuters 27 April 2004.

[24] The first three were requested to each pay 2.37 million yen (US$21,000). “Former Japanese,” ibid.; the next two, about US$500. Tama Miyake Lung, “Former Iraq hostage Jumpei Yasuda eager to go back,” Japan Today, 7 June 2004. This author has no information on whether any of the payments were actually made. According to an interview with Takato in September, 2004, she was planning to pay only for her ticket from Baghdad to Dubai following negotiations between her lawyers and the Foreign Ministry. See Matsumoto Chie, “Bouncing Back: Former Iraq Hostage continues Humanitarian Battle,” IHT/Asahi Shimbun, 18 September 2004, also at Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

[25] Tom Plate, “The Power of Asian Values [column],” The Los Angeles Times, 28 April 2004.

[26] Norimitsu Onishi, “Japanese are Cold to Freed Hostages,” The International Herald Tribune, 23 April 2004.

[27] Cited in “Perception Gap: Debate Swirls over Hostages’ Responsibility,” The Asahi Shimbun, 21 April, 2004, 21.

[28] Bashing, dir. Kobayashi Masahiro (Monkey Town Productions, 2005).

[29] John Dower, cited in Kathleen Krauth and Lynn Parisi, “An Interview with John Dower,” Education About Asia 5, no. 3 (Winter 2000); also, John W. Dower,Japan in War and Peace: Selected Essays (New York: New Press, 1993), 274.

[30] Dower 1993, ibid., 274.

[31] Dower, cited in Krauth and Parisi, ibid.

[32] Cited in Andrew Marshall, “Briton among 11 Hostages Seized in Iraq,”Reuters UK Online, 8 April 2004.

[33] The salvo of hostage-takings that began in the spring of 2004 was preceded by America’s shutdown of the Al-Hazwa newspaper, on 28 March (three days before the killing of the four American contractors and ten days before the capture of Imai, Koriyama and Takato). Coalition authorities would not tolerate the newspaper because it was controlled by the Shiite cleric, Muqtada al-Sadr, Al-Hazwa, whom Americans feared had the capacity to “incite violence.” This un-democratic action led to widespread protests and disastrous loss for the American-led coalition; nearly 40 Americans and 300 Iraqis were killed. The subsequent hostage-takings continued for the next two years to such an extent that the abductee became an icon of the war itself as well as an indication of the war’s global reach. The Hostage Working Group showed that as of May 2006, 439 foreigners of 60 nationalities and several professions were abducted; 18% of those killed. See Erik Rye and Joon Mo Kang, “Hostages of War,” International Herald Tribune, 18 May 2006, 8.

[34] Takato Nahoko, Senso to heiwa: soredemo Irakijin wo kirai ni narenai [War and peace: or, why I still won’t hate the Iraqi people] (Tokyo: Kodansha, 2004), 66.

[35] Takato, Senso to heiwa, ibid., 64-68.

[36] “Editorial,” IHT/The Asahi Shimbun, 19 April, 2004 [original published in vernacular on 4/18/04), 21.

[37] Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), Message from Ms. Yoriko Kawaguchi, Minister of Foreign Affairs, to the members of the Saraya-Al-Mujahadeen. 10 April, 2004.

[38] Tom Raum, “Cheney to urge Japan to stay course in Iraq,” Washington Times [Associated Press], 12 April 2004.

[39] National Association of Japan-America Societies, “Japan-America 150th Anniversary: A Commemorative Ceremony and Exhibit.”

[40] Howard Baker, Jr., The Best Team, U.S. Department of State United States Embassy: Japan Official Homepage 25 March 2004.

[41] Cited in Reiji Yoshida, “Families Opposed to U.S. Rescue Operation, The Japan Times, 11 April 2004, 1.

[42] “Public is split over policy not to pull out SDF: survey,” The Japan Times, 11 April 2004, 2.

[43] Cited in “Perception Gap: Debate Swirls over Hostages” Responsibility, ibid., and “Hostages ‘Anti-Japan’: Lawmaker,” The Japan Times, 27 April, 2004.

[44] I am grateful for the summary of this news provided by Fumiko Halloran, [Listserve] Shukan Shincho on Japanese NBR’S JAPAN FORUM (POL), 23 April, 2004, retrieved on 1 May 2004.

[45] The Islamic Clerics Committee that arranged the release said that it would occur in 24 hours, although the actual release of the hostages was a few days later. Some believed a report originally put out by Radio France that the delay was a result of Koizumi’s depiction of the hostage-takers as terrorists, when he rejected the demands of the militant group to pull troops out Iraq by saying, “We will not bow to any despicable threat by terrorists.” Cited in Kyodo World Service, 13 April 2004; retrieved on 16 April 2004.

[46] “Highlights of Captors’ Statement on Freeing Japanese Hostages,” Kyodo News on the Web 11 April 2004.

[47] See 2channeru (2 channel) (bulletin board), comments on 11 April 2004.

[48] Cited in Brad Glosserman, “U.S.-Japan Relations: Mr. Koizumi’s Payback,” Pacific Forum CSIS.

[49] Tachibana, ibid., 28-29.

[50] Cited in “Hostages ‘Anti-Japan,’” 2004, ibid.

[51] “Former Japanese Iraq Hostages Criticize Media,” ibid.

[52] Cited in Tama Miyake Lung, “Former Iraq hostage Jumpei Yasuda eager to go back,” Japan Today, 7 June 2004.

[53] Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, “Iraq and the Media: A Critical Timeline,” 19 March 2007.

[54] Chris Matthews, MSNBC, 1 May 2003, cited in Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, ibid.

[55] Newsweek.com, 22 April 2003, cited in Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, ibid.

[56] In a worst-imagined scenario, an Al-Jazeera correspondent, a Reuters reporter, and thirteen members of the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross) were all killed on 8 April 2003 by American fire, presumed by some critics to have been actually “targeted” because of their independent, non-embeddedness. Michel Chossudovsy, “Killing the ‘Unembedded Truth,’” Center for Research on Globalisation, 11 April 2003; retrieved from. The United States has acknowledged that three Reuters reporters were killed by their own forces, though they claim the soldiers fired with justifiable reason. Other journalists have been illegally detained or abused by American soldiers, according to Reuters Global Managing Editor, David Schlesinger, who has called on the United States to recognize the “legitimate rights of journalists in conflict zones under international law.” In his statement to the U.S. Armed Services Committee, Schlesinger states, “The worsening situation for professional journalists in Iraq directly limits journalists’ abilities to do their jobs and, more importantly, creates a serious chilling effect on the media overall.” Barry Moody, “Reuters says US Troops Obstruct Reporting of Iraq,” Reuters, 28 September 2005.

[57] Reporters Without Borders (homepage).

[58] Douglas Kellner 2005, ibid., 66-67.

[59] Douglas Kellner, “Spectacle and Media Propaganda in the War on Iraq: A Critique of U.S. Broadcasting Networks”, online at the Institution of Communication Studies, University of Leeds [circa 2003].

[60] Douglas Kellner 2005, ibid., 66. As CNN correspondent Tim Mintier expressed it, the American officials “buried the lead” in an attempt to manage the news that was becoming more and more perceptible at the time. Mintier’s views are featured in the documentary film, Control Room, dir., Jehane Noujaim (Magnolia Pictures, 2003).

[61] Bush and others referred to the twelve low-ranking officers serving prison sentences for abuse as “bad apples”; the guards are now appealing their sentences. See “’Abu Ghraib US Prison Guards were Scapegoats for Bush,’ Lawyers Claim,” Times Online, 2 May 2009; references to “night shift” were also frequent among Bush officials, and the expression, “Animal House on the night shift” attributed to former Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger who chaired an independent panel on the prisoner abuse scandal. See “The Investigations,” PBS Frontline, The Torture Question, 2005.

[62] “Interview: Mark Danner,” PBS Frontline, The Torture Question, ibid.

[63] “Torturefest and the Passage to Pedagogy of Tortured Pasts,” in François Debrix and Mark J. Lacy, eds., The Geopolitics of American Insecurity (London: Routledge, 2009), 71-87.

[64] Iraq Hope Network. Excerpts from Imai’s memoir, with a substantive introduction by Norma Field, can be found at Imai Noriaki, “Why I went to Iraq: Reflections of a Japanese Hostage,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 29 December 2007.

[65] Iraq Hope Diary.

[66] “Limbaugh on Kidnapping of Peace Activists in Iraq,” Media Matters, 30 November 2005.

[67] See also the “Appeal on Behalf of the Hostages to the Sara Al Mujahedeen,” featured in Imai Noriaki, “Why I went to Iraq,” ibid.

[68] Robert Zelnick, “Jill Carroll and the Politics of Terrorism,” The Guardian Unlimited, 31 March 2006.

[69] I have no definitive information on the extent to which the release of either the Japanese hostages or Carroll was influenced by such private efforts, since governments are typically secretive about such matters, but in both cases the paper trail of private support was substantial.

[70] Highlights from the blogosphere available at Melonyce McAfee, “Female Trouble,” Slate, 30 March 2006.

[71] Bernard McGuirk, executive producer of “Imus in the Morning”, who regularly antagonizes the radio/television program’s regular host, Don Imus. Citation and video available at Think Progress.

[72] A later hostage incident involving a Japanese yielded different results. Seven months after the release of the five Japanese hostages, a 24-year old Japanese ESL student in New Zealand traveled to Jordan for adventure. On a whim, or for reasons unknown, Koda Shosei crossed the forbidden line into Iraq. He was captured immediately. His captors, this time a different brigade, issued a video with a statement threatening to kill him if Japan did not withdraw its troops. Though Koda had transgressed, the Foreign Minister (Machimura) responded swiftly; while not dispatching troops, government officials claimed to do what they could to secure the release of the young man. Their efforts failed, however, and Koda was beheaded. This time, however, the issue received comparatively little coverage and was overshadowed by Japan’s worst earthquake in a decade. Koda was not known for any politically controversial actions or statements. Neither the presence of the American coalition, nor the US-Japan alliance itself, was at a crucial moment of testing.

[73] On media common places, see Paulo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude: For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2004), 38-44.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.