From National Security Archive

Washington, DC, November 1, 2020—President John F. Kennedy was more disposed to support the removal of South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem in late 1963 than previously appeared to be the case, according to a recently released White House tape and transcript. The ouster of Diem in a military coup that would have major implications for American policy and growing involvement in the country happened 57 years ago today. Even now the views of Kennedy and some of his top aides about the advisability of a coup specifically have been shrouded by an incomplete documentary record that has led scholars to focus more on the attitudes of subordinates. Today, the National Security Archive is posting for the first time materials from U.S. and Vietnamese archives that open the window into this pivotal event a little bit wider.

Kennedy’s views on removing Diem become more explicit in a tape recording of his meeting with newly-appointed Ambassador to Saigon Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., in mid-August 1963, just before Lodge set out for Saigon. Other records published today, including NSC notes of White House meetings and CIA field reports from South Vietnam, allow for a broader look at the coup period and the roles of on-the-ground officials such as the CIA’s Lucien Conein and Ambassador Frederick Nolting. Some of these materials first appeared in earlier National Security Archive E-books and are added here to provide the larger context of events.

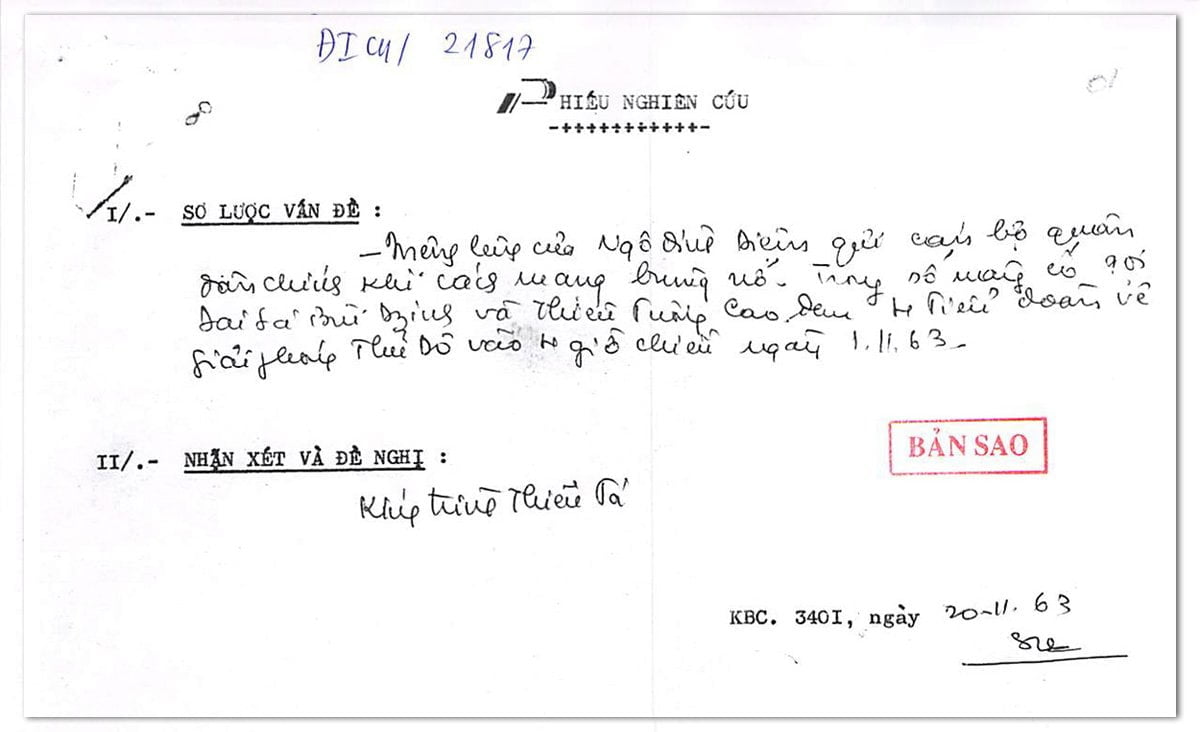

Today’s posting also features a dramatic handwritten proclamation on November 1, 1963, from the doomed Diem demanding that the South Vietnamese Army follow his orders. But within hours he would be deposed and 24 hours later summarily executed by the military. Author Luke A. Nichter found the document in the Vietnamese archives. He co-authored today’s posting with Archive Fellow John Prados.

* * * * *

The coup against Diem has been a much-debated passage in the history of the American war in Vietnam. The National Security Archive has participated in these debates by introducing important new evidence and interpretation. In 2003 we posted an electronic briefing book with one of the first-released Kennedy tape recordings of a key White House deliberation on the final go-ahead for the coup. That post included a selection of essential documents, including the CIA briefing where the agency’s director, John McCone, informed the president of the initial approaches by South Vietnamese plotters to CIA officers. The South Vietnamese demands for American support became more insistent in the second half of August, 1963, and the posting presented the National Security Council (NSC) and State Department records of a series of White House meetings and other U.S. deliberations over a coup in Saigon. A big issue, then and since, has been the so-called “Hilsman Telegram,” or, more formally, Department Telegram (DepTel) 243, which instructed U.S. Ambassador to Saigon Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. to proceed in a fashion that made clear to Diem that he needed to end nepotism and curtail the activities of his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, and other family members, whose efforts were impeding the counterinsurgency war then in progress. The E-book contained a selection of documents that showed how Washington considered South Vietnamese who might be alternative candidates for leadership, and jumped ahead to the final days before the coup.

In 2009 the Kennedy Library made a release of the tapes that actually covered the White House conversations of late August. The Archive built an E-book around those audiotapes, too, starting with DepTel 243 and then permitting the reader/listener to make extensive comparisons, by pairing the White House tapes with the NSC and State Department memoranda recording those same conversations. In one case we also had a record made by a senior Pentagon participant, Major General Victor Krulak. This supplemented the earlier electronic briefing book.

Diem’s handwritten proclamation to the Army on the day of the coup, November 1, 1963 (Document 26).

We have since continued to collect material, and Luke Nichter’s presentation of the Kennedy-Lodge tape from mid-August offers a good opportunity to revisit the coup. Here we step back to take a broader view, not just focusing on the events of August but on the full panoply. Among the items we present here are the audio and transcript of the president instructing his ambassador; notes taken during the key week by Thomas L. Hughes, director of the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research; the handwritten notes on White House meetings by NSC staff deputy Bromley K. Smith; a wider selection of meeting notes from General Krulak; the CIA summary of meetings between its officers and the Vietnamese generals; a selection of CIA field reports, including the early October Vietnamese mention of assassination and the CIA reaction to that; and several items from the immediate period of the coup and assassination, including a desperate appeal for aid from President Diem even as the coup against him was underway.

Among the findings from the present posting or from our several Diem E-books taken together are the following:

- President John F. Kennedy was more disposed, than previously understood, to support actions that might change the leadership in South Vietnam.

- Kennedy was personally aware of the pro-Diem views of Frederick E. Nolting, Lodge’s predecessor as ambassador, strengthening the impression that he included Nolting in White House deliberations—and personally engaged him in colloquy about Saigon events—partly to build a case that all sides in this debate had been heard.

- White House conversations took place without any principal figures changing their minds about the Saigon situation.

- When South Vietnamese military officers renewed their contacts with CIA operatives in early October, the Vietnamese immediately raised the option of assassination.

- Vietnamese figure Ngo Dinh Nhu, brother of leader Diem, remained the prime target of American maneuvers. Nhu’s attempts to fend off criticism or ingratiate himself with Washington failed.

* * *

DISCUSSION

Vietnam perplexed American leaders from Franklin D. Roosevelt on. By the time John F. Kennedy was president, the situation seemed hopeful for a moment—long enough for JFK to think of Vietnam as a sort of laboratory where he could try out tactics and techniques. By this juncture, 1963, that optimism had evaporated and Kennedy felt that obstructionists in Saigon were losing ground against a communist insurgency. When, that May, Ngo Dinh Diem’s government got into a political confrontation with Vietnamese Buddhists, American frustration increased. So did South Vietnamese. A Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) operative was approached during the time of U.S. 4th of July festivities by South Vietnamese military officers who wanted U.S. support for a coup d’etat that might overthrow Diem (2003 E-book, document 1).

This present E-book opens (Document 1) with the record of a July 19, 1963, encounter between CIA Station Chief John Richardson and Diem’s brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, who ran many of South Vietnam’s special services and was increasingly seen as the power behind the presidency. This shows that Nhu, even when “calm,” as Richardson observes, obsessed with Buddhists spreading propaganda and hiding communist agents among their monks at some of the most important pagodas. Nhu had begun weekly meetings with the generals of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) where he himself had introduced the subject of a coup—as he told the CIA, it was a “psychoanalytic” technique which might induce the ARVN officers to reveal their intentions.

Nhu continued his plotting, which eventually led to a plan to launch government raids against the most important Buddhist pagodas in Saigon and Hue (Document 5).

President Kennedy decided to replace his ambassador to Saigon, Frederick E. Nolting, and appointed Henry Cabot Lodge to that position. Lodge and Kennedy met in the Oval Office on August 15 (Item 2, Document 3). We present both the audio of that meeting and a transcription of it crafted by Luke Nichter. These materials reveal that Lodge already held nuanced views on the situation in South Vietnam and had already met with South Vietnamese representatives in the U.S., who happened to be the parents of Ngo Dinh Nhu’s wife. Kennedy did a lot of agreeing, letting Lodge talk, but the two concurred the press in Saigon posed a problem, JFK expressed the sense that something would have to be done about Diem, but he didn’t want to be driven to that by the press, and he was not yet certain who, other than Diem, the U.S. could support in Saigon. Kennedy wanted Lodge to make a personal assessment.

Lodge left for Saigon, planning to stop in Hawaii and Japan on his way to receive various briefings and touch base with senior U.S. officials. During his trip the Saigon situation escalated as Nhu went ahead to launch the raids on the Buddhist pagodas he had already planned. At the State Department, W. Averell Harriman and George Ball agreed that Lodge ought to delay his arrival in Saigon until the situation had calmed somewhat (Document 4). He actually reached Saigon two days after their conversation (August 23, Washington date). He had no time to acclimate. The CIA’s chronology of its contacts with ARVN plotters (Document 13) shows that the initial contacts which plunged Washington into a frenzy of deliberations on whether to support a coup in Saigon occurred that day. One day later, Ambassador Lodge received the infamous DepTel 243, the “Hilsman cable” (2003 E-book, Document 2; E-book 302, Document 1). We do not reproduce this here because we presented it in both the previous electronic briefings on this subject. News of ARVN’s request for backing of a coup reached Kennedy as his president’s daily brief (then called the President’s Intelligence Checklist, or PICL) was reporting that Ngo Dinh Nhu was indeed behind the Pagoda Raids, and that Nhu and Diem were issuing direct orders to military officers, leaving out the ARVN chain of command (Document 7).

In our 2003 and 2009 postings, and the 2013 update, the story of what Kennedy and his officials actually decided about the Saigon coup in August was at the heart of our inquiry. Rather than revisit all of that debate, here we want to touch on a few points, presenting nuances in the form of the Thomas Hughes notes (Document 6) and meetings with Diem and Nhu that were taking place within this timeframe (Documents 8, 14, 15), amplifying the evidence.

The tapes of the White House meetings on August 26, 27, and 28, along with written records of those meetings made by NSC notetaker Bromley K. Smith and State Department official Roger A. Hilsman are available in the earlier postings, along with one record by General Victor H. Krulak. Here we add Krulak’s records on the other meetings (Documents 9, 11) and Bromley Smith’s handwritten notes, from which he derived the records we had previously posted (Documents 10, 12). Together, these materials offer comprehensive documentation on the Kennedy administration’s August coup talk.

The cycle of meetings opened on Monday, August 26, after the Hilsman cable had been sent and when the object was whether to confirm the instruction it had contained. The received history on this is that Hilsman, Harriman, and NSC staffer Michael Forrestal advocated going ahead with a coup, while other factions opposed it. One opposition faction centered on former Ambassador Nolting. Military opponents coalesced around General Maxwell D. Taylor, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and included General Krulak; while another center of opposition included CIA Director John McCone and his responsible division chief, William E. Colby. President Kennedy acted mostly as moderator. He regarded Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy as other opponents.

As we demonstrated in our 2009 E-book the reality was more complex. Bobby Kennedy spoke little in the August meetings and was absent from the August 26 session, when anger over the Hilsman cable should have been most focused. Instead, JFK spoke not of opposing a coup, but of not conducting one just because the New York Times was pushing it—almost a repeat of what he had expressed to Lodge in their meeting 10 days earlier (Document 3). Hilsman dominated the discussion, with Taylor doubting whether Saigon could get along without Diem, and McNamara sought assurances on four points. He also wanted to see something on Lodge actually talking with Diem. That encounter actually took place at that very time (Document 8). Secretary of State Dean Rusk remarked that “we’re on the road to disaster,” posing the alternatives as whether to move U.S. troops into Vietnam or get our resources out. This amounted much more to a quest for more information on Saigon conditions than an assault against a purported pro-coup faction.

On August 27 Ambassador Nolting took center stage. Our additional records do not change the impression we expressed in 2009 that Nolting had essentially gone native (Documents 9, 10). He represented the Pagoda Raids as some sort of victory for Diem, absolved Nhu of responsibility for them, pictured Diem as a man of integrity who had tried to carry out all the promises he had made to the United States, and framed Vietnamese Buddhism as manipulated by Cambodia. Nolting conceded that Nhu—also a “man of integrity”—had become a liability, but he rejected the proposition the Vietnamese generals would carry out a coup. John F. Kennedy notably remarked there was no point to a coup if it would not work.

The next day, Nolting added that the notion of a coup was based on a bad principle and would set a bad precedent, a statement that impressed National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy (Documents 11, 12). The former ambassador argued that no one other than Diem could keep South Vietnam together. CIA Director Colby described a Saigon situation that pictured the pro-regime forces as stronger than the plotters. He also spoke of how in a previous coup (1960), time had played in favor of Diem, not against him. George Ball argued that Nhu in the ascendant was impossible to live with, making the coup imperative, but the questions were mooted that day when the Vietnamese generals postponed their coup plot.

August deliberations had the effect of enabling top U.S. officials to rehearse all the arguments for and against a coup, but they left Washington with its policy problem—the intractability of Saigon leaders closed off the potential for progress in Vietnam. The experience of Americans in South Vietnam established that. Presenting his credentials to Diem on August 26 (Document 8), Ambassador Lodge got 10 minutes to explain the role of public opinion in setting U.S. policy, advising that the Saigon leader release Buddhist prisoners, after which Diem minimized the importance of Buddhists, then treated him to a two-hour harangue on his family and South Vietnam as an underdeveloped country.

Just as Kennedy ended the August round of coup talks, State Department official Paul Kattenburg, who had known Diem for a decade, had his own experience (Document 14). Kattenburg got the impression the man had a growing neurosis. “More than on earlier occasions,” he recorded, Diem “talked largely to himself.” The Saigon potentate defended his stance in the Buddhist crisis, and defended his brothers Nhu and Thuc, the archbishop of Hue, whose antics had touched off the crisis. Diem made conflicting claims that the Buddhists were being stirred up by communist cadres and that the crisis was entirely solved. For his part, Nhu also came off as more and more ominous (Document 15). The CIA learned of a talk he had had with ARVN commanders in the Saigon area where Nhu asserted that a cutoff of foreign aid would not be a problem because South Vietnam had enough foreign currency reserves to continue for 20 years. Nhu ordered that ARVN soldiers be instructed to open fire on any foreigners involved in “provocative acts.”

American officials differed on who might follow Diem and Nhu in leading Saigon. Unlike Nolting, who saw no possible candidates, the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) produced an extensive list (Document 16). They emphasized, “we believe that Vietnam is not faced with any serious shortage of effective non-Communist leadership.” Thomas L. Hughes, INR’s director, remains proud today of the list his experts assembled in 1963.[1] The next day, INR went ahead to craft a paper on “The Problem of Nhu” (Document 17), where analysts cited South Vietnamese opinions that Nhu had become the dominant power in Saigon, exercising “an overriding, immutable influence over Diem.”

Kennedy’s associates concluded early on that Ngo Dinh Nhu had to go. If President Diem refused to jettison Nhu, then Diem would have to go as well. That was the sense of the Hilsman cable, and of the follow-up instruction sent after the August round of coup talk. Through September and October, even as Washington sought to make its point by considering evacuation of U.S. nationals, withdrawals of American troops, and halting CIA aid to South Vietnamese Special Forces, President Kennedy tried to understand the situation better. JFK sent a succession of study groups to Saigon—Huntington Sheldon of the CIA, Robert McNamara plus Maxwell Taylor, General Krulak plus Joseph Mendenhall—all to report to him. The visits all confirmed what INR had said in its “Problem of Nhu” memorandum (Document 17).

Silence from the Vietnamese generals made Washington officials wary of getting too far ahead of Saigon politics. That was one reason for the study missions. Rufus Phillips describes one White House meeting around this time that ended in complete pandemonium.[2] In an EYES ONLY cable on September 15, Secretary Rusk warned Ambassador Lodge that the coup envisioned in the Hilsman cable was “definitely in suspense” and that no effort should be made to stimulate any coup plotting. Decisions had yet to be made in Washington.[3] At the same time Lodge was involved in a spat with the CIA over changing its station chief in Saigon. That was the climate in which ARVN General Tran Thien Khiem asked CIA for a meeting. The contact, and the meeting which followed, tipped the Americans to Nhu’s maneuvers to create channels to Hanoi, reminded them that coup plans still existed, and informed CIA that the generals were awaiting Diem’s response to their demands for cabinet-level positions in the South Vietnamese government (Document 13).[4]

By that time Secretary McNamara and General Taylor were in Saigon on their fact-finding mission. They spoke with academic Vietnam experts, the CIA station chief, and President Diem. Taylor wrote a lengthy report afterwards which argued the generals had “little stomach” for government and had been neutralized.[5] But almost simultaneously in Saigon, the CIA electrified Washington when operative Lucien Conein ran into General Tran Van Don at the airport and the two held a meeting that night where the ARVN officer affirmed that the generals now had a specific plan, and Don got Conein to agree to meet the top plotter several days later.[6] Document 18 is the record of Conein’s encounter with General Duong Van Minh on October 5. General Minh renewed the August call for an expression of U.S. support for a coup. Minh identified the principal plotters, assured the CIA man a coup would take place in the near future, and outlined several possible coup options. One of them—the “easiest,” Minh said—was to assassinate two of Diem’s brothers while keeping Diem himself as a figurehead.

The mention of assassination occurred at a key moment for the U.S. in Saigon. Ambassador Lodge was sending home his CIA station chief. The assistant chief, left to comment on General Minh’s options, advised Washington not to dismiss the assassination too quickly, as the other possibilities basically meant civil war.[7] This advice outraged CIA Director McCone and Far East operations chief Colby. McCone shot back that the best line was no line. Years later, when the Church Committee was investigating the CIA (in 1975), McCone quoted himself telling John F. Kennedy, in precise words that he remembered very clearly, “Mr. President, if I was manager of a baseball team, [and] I had one pitcher, I’d keep him in the box whether he was a good pitcher or not. By that I was saying that, if Diem was removed we would have not one coup . . . but a succession” (Document 20).[8] McCone ordered Saigon station to drop the suggestion, and the next day Colby reinforced that order with another (Document 19).

From that point on, the U.S. embassy and Saigon station became even more active as observers of South Vietnamese coup preparations. There were more contacts with the Vietnamese generals. At one point Ambassador Lodge personally assured General Tran Van Don that CIA operative Conein was speaking authoritatively for the U.S. embassy.[9]

Lodge had an active role in disentangling one of the most important obstacles to the coup when the South Vietnamese were moving into position. On October 23, Don had another get-together with CIA’s Conein (Document 21) where he demanded assurances on the U.S. stance and the intelligence officer was able to answer in a way that satisfied Washington guidelines. The coup would take place in a window of late October-early November. Don was furious that a different, subordinate ARVN officer, talking of a different coup, had been discouraged by U.S. military group commander General Paul D. Harkins, while word of that had reached President Diem. In turn, Conein challenged Don to produce proof that the coup group was actually authentic. Back at the embassy Lodge confronted Harkins over his intervention with the South Vietnamese officer (Document 22). Lodge set Harkins straight that the United States, while not initiating any coup, was to avoid any action that thwarted or opposed a coup. On October 24 (Document 23) Conein met again with Don, who confirmed that Harkins had admitted his error in seeming to oppose a coup. Don asserted that all plans were complete and had been checked and re-checked.

Washington’s last opportunity to back out of the Saigon coup occurred on October 29, when President Kennedy gathered his advisers to go over the ground one more time. The National Security Archive documented this event in some detail in our 2003 electronic briefing book, where we presented the meeting agenda, a tape of the conversation, the NSC meeting record, and two draft cables to Saigon that the participants considered (2003 E-book, Documents 18, 19, 20, and 21 plus audio clip). Here we present Roger Hilsman’s record of that meeting from State Department files (Document 24). At this late date Bobby Kennedy still opposed the coup and Maxwell Taylor sided with him, while other officials looked ahead to the composition of a future Saigon government, or focused on tactics or the balance of forces on the coup and palace sides.

Contrary to fears expressed at the October 29 White House meeting, when the coup began on November 1, President Diem and his forces were fairly quickly corralled in the Gia Long Palace. Again, the 2003 E-book presented an array of materials on these events (Documents 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28), ranging from Kennedy’s White House sessions to monitor events, to the CIA daily situation reports, to a cable relating several versions of how Diem and Nhu died, to a CIA retrospective analysis of press coverage of the deaths. Here we supplement the 2003 coverage with some new evidence. On November 1 we have the PICL which shows the coup underway (Document 25). Desperate to save himself, amid the coup fighting, President Diem drafted a proclamation ordering the army to reject all but his own orders and summoning help from loyal forces outside Saigon (Document 26). But it was too late. The PICL of November 2 (Document 27) records that Diem and Nhu had been killed.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.