From National Security Archive

Washington D.C., November 3, 2020 – Several days after Salvador Allende’s history-changing November 3, 1970, inauguration, Richard Nixon convened his National Security Council for a formal meeting on what policy the U.S. should adopt toward Chile’s new Popular Unity government. Only a few officials who gathered in the White House Cabinet Room knew that, under Nixon’s orders, the CIA had covertly tried, and failed, to foment a preemptive military coup to prevent Allende from ever being inaugurated. The SECRET/SENSITIVE NSC memorandum of conversation revealed a consensus that Allende’s democratic election and his socialist agenda for substantive change in Chile threatened U.S. interests, but divergent views on what the U.S. could, and should do about it. “We can bring his downfall, perhaps, without being counterproductive,” suggested Secretary of State William Rogers, who opposed overt hostility and aggression toward Chile. “We have to do everything we can to hurt [Allende] and bring him down,” agreed the secretary of defense, Melvin Laird.

“Our main concern in Chile is the prospect that [Allende] can consolidate himself and the picture projected to the world will be his success,” President Nixon explained as he instructed his national security team to adopt a hostile, if low-profile, program of aggression to destabilize Allende’s ability to govern. “We’ll be very cool and very correct, but doing those things which will be a real message to Allende and others.”

Marking the 50th anniversary of Salvador Allende’s inauguration, the National Security Archive today posted a collection of documents that provide a detailed record of how and why President Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, established and pursued a policy of destabilization in Chile—operations that “created the conditions as best as possible,” as Kissinger later put it, for the September 11, 1973, military coup that brought General Augusto Pinochet to power. The detailed deliberations and decisions they contain clarify the misrepresentations by former policy actors over the years, Kissinger among them, of the true intent of the Nixon administration posture toward the Allende government. A half century after the inauguration, according to the Archive’s senior analyst on Chile, Peter Kornbluh, “these documents record the deliberate purpose of U.S. officials to undermine Salvador Allende’s ability to govern, and ‘bring him down’ so that he could not establish a successful, and attractive, model for structural change that other countries might emulate.”

When the CIA’s covert operations to undermine Allende were revealed on the front page of the New York Times in September 1974 by veteran investigative reporter Seymour Hersh they generated a major national and international scandal. The uproar over the clandestine U.S. role in Chile led to the first substantive congressional inquiry into U.S. covert operations, the first public hearings on CIA operations, and the first publication of a major case study, Covert Action in Chile, 1963-1973, written by the special Senate committee chaired by Senator Frank Church. “The nature and extent of the American role in the overthrow of a democratically elected Chilean government are matters for deep and continuing public concern,” Senator Church stated at the time. “This record must be set straight.”

But, asserting “executive privilege,” the administration of Gerald Ford withheld some of the dramatic documentation posted today from the Church Committee. As U.S. officials sought to falsify the purpose of U.S. intervention in Chile, Senate investigators did not have access to the complete historical record on the White House deliberations and decisions on Chile in the days before and after Allende’s inauguration.

The Official Narrative

In the immediate aftermath of the Hersh revelations, President Ford issued an unprecedented, if mendacious, acknowledgement of CIA covert operations. “The effort that was made in this case,” he told the press, “was to help assist the preservation of opposition newspapers and electronic media and to preserve opposition political parties.” U.S. intervention to preserve Chile’s democratic institutions was “in the best interests of the people of Chile and certainly in our best interests,” President Ford submitted as the Pinochet regime marked the first anniversary of what would become a 17-year military dictatorship.

In testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Henry Kissinger advanced this “preservation of democracy” rationale. “The intent of the United States was not to destabilize or to subvert [Allende] but to keep in being [opposition] political parties….Our concern was with the election of 1976 and not at all with a coup in 1973 about which we knew nothing and [with] which we had nothing to do.” Kissinger reiterated this argument in his memoirs, The White House Years.

Other former U.S. officials who participated in the anti-Allende operations also used their memoirs to re-write the history of U.S. intervention in Chile. In Good Hunting: An American Spymaster’s Story, published in 2014—and excerpted in the pages of the prestigious journal, Foreign Affairs under the title “What Really Happened in Chile”—the former CIA officer Jack Devine asserted that the CIA was merely “supporting Allende’s domestic political opponents and making sure Allende did not dismantle the institutions of democracy.” The goal, according to Devine, was to preserve those institutions until Chile’s 1976 election when those democratic forces, bolstered by covert U.S. support, would prevail over the evils of Allende’s Popular Unity coalition.

The “preservation of democracy” rationale made for good spin, but it is completely disproven by the declassified White House records. Those records reveal that the U.S. State Department, which feared an international scandal if U.S. efforts to overthrow Allende were exposed, argued for a prudent policy of co-existence—known as the “modus vivendi strategy”—while supporting the opposition parties and bolstering their chances of prevailing in the 1976 election. If Washington violated its own pronounced policy of “respect for the outcome of democratic elections,” the Bureau of Inter-American Affairs argued in one briefing paper during the internal debate over how to respond to Allende’s inauguration, it would “reduce our credibility around the world … increase nationalism directed against us,” and “be used by the Allende Government to consolidate its position with the Chilean people and to gain influence in the rest of the hemisphere.”

But the documents also reveal that Kissinger forcefully rejected that option, and personally convinced President Nixon to overrule it in favor of an effort to destabilize Allende’s ability to govern. “It is essential that you make it crystal clear where you stand on this issue,” Kissinger privately lobbied Nixon in preparation for the November 6 NSC meeting on Chile. “If all concerned do not understand that you want Allende opposed as strongly as we can, the result will be a steady drift toward the modus vivendi approach.”

Kissinger’s Arguments

The documents record that Kissinger was the prevailing influence for a sustained effort to destabilize and undermine Allende. As it became clear to him that the CIA’s efforts to foment a coup before Allende’s November 3 inauguration would likely fail, Kissinger presented Nixon with his initial arguments for a long-term aggressive approach that would be masked in its hostility. “Our capacity to engineer Allende’s overthrow quickly has been demonstrated to be sharply limited,” he wrote in a secret briefing paper on October 18, 1970:

The question, therefore, is whether we can take action—create pressures, exploit weaknesses, magnify obstacles—which at a minimum will either insure his failure or force him to modify his policies, and at a maximum might lead to situations where his collapse or overthrow later may be more feasible.

Kissinger posed two potential approaches for a hostile strategy:

—One would be a frankly overtly hostile policy, utilizing all possible pressures and demonstrating that hostility openly;

—The other would be a publicly “correct” but cold posture, with pressure and hostility supplied non-overtly and behind the scenes, and hostile measures demonstrated publicly only in reaction to provocation.

“Both courses” he submitted, “would use essentially the same measures—e.g., CIA activity, economic and diplomatic pressures. The difference—and the issue—lies in the question of how overt our hostility should be.”

As the National Security Council prepared to meet in early November, on October 29, Kissinger chaired a meeting of the Senior Review Group to determine what options on Chile would be presented for President Nixon’s final consideration. The Defense Department representatives advocated an overtly hostile approach; the State Department members cautioned against overt aggression, and pressed for a more flexible approach that held out the “option of establishing friendly relations with Allende in the event, now considered unlikely, that he moderates his Marxist and authoritarian objectives,” according to minutes of the meeting. The CIA, represented by Director Richard Helms, head of covert operations Thomas Karamessines, and the chief of Western Hemisphere operations, William Broe, supported a hostile approach, through covert operations, to undermine Allende. For security reasons, the covert action plan they drew up to destabilize Chile was classified as a special annex to the options papers and not distributed to the other agencies.

Assuring that the hostile approach prevailed was so important to Kissinger that he arranged for the NSC meeting to be postponed by a full day, so that he could get into the Oval Office for an hour to brief Nixon on how he should push the foreign policy bureaucracy toward a regime change posture. “Henry Kissinger came in this morning to try to see if we could move the NSC Meeting to Friday. He feels this is very important because the subject matter is Chile and Henry says it is imperative that the President study the issue prior to holding the meeting,” stated a memo to Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman from Nixon’s scheduler, explaining why the meeting was being moved from November 5 to November 6. “According to Henry, Chile could end up being the worst failure in our administration—’our Cuba’ by 1972.”

For his private meeting with Nixon, Kissinger drew up a comprehensive memo outlining “the serious threats to our interests and position in the hemisphere” and beyond that Allende represented—as well as the threat of the State Department’s position that the U.S. should adopt “a modus vivendi strategy” with an Allende government and focus on defeating him in the next election in 1976. The document, first published in Peter Kornbluh’s book, The Pinochet File, on the 40th anniversary of the coup, provides the most comprehensive explanation for U.S. intervention in Chile of any of the thousands of declassified records in the public domain.

“The election of Allende as President of Chile poses for us one of the most serious challenges ever faced in this hemisphere,” Kissinger wrote in his opening sentence, underlining it for effect. “Your decision as to what to do about it may be the most historic and difficult foreign affairs decision you will have to make this year,” he dramatically advised Nixon, “for what happens in Chile over the next six to twelve months will have ramifications that will go far beyond just US-Chilean relations.”

As reflected in the briefing paper, Kissinger’s key concern about Allende was that he had been freely elected, leaving the United States with little latitude to openly oppose his government as illegitimate, and setting a precedent that other nations might follow. Allende’s “model effect can be insidious,” Kissinger warned: “The example of a successful elected Marxist government in Chile would surely have an impact on—and even precedent value for—other parts of the world, especially in Italy; the imitative spread of similar phenomena elsewhere would in turn significantly affect the world balance and our own position in it.”

He lobbied Nixon to reject the State Department modus vivendi option, and instruct the National Security Council to implement a hostile policy to undermine Allende, but masked as benign diplomatic coolness toward his government. “The emphasis resulting from today’s meeting must be on opposing Allende and preventing his consolidating power and not on minimizing risks,” Kissinger advised Nixon.

At the NSC meeting the next day, Nixon parroted Kissinger’s talking points on the threat of the “model effect” that Allende represented. “We’ll be very cool and very correct, but doing those things which will be a real message to Allende and others,” he advised his national security team, according to the SECRET memorandum of conversation of the meeting. According to declassified notes taken CIA Director Helms at the meeting, the president also advised that “If there [is] any way to unseat A [llende], better do it.”

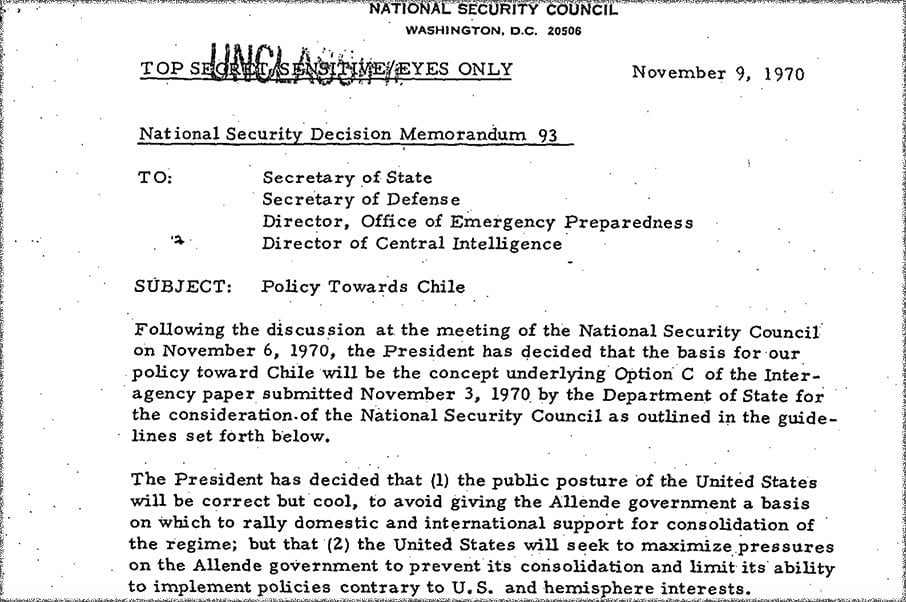

Six days after Salvador Allende’s inauguration, Kissinger distributed a TOP SECRET/SENSITIVE/EYES ONLY National Security Decision Memorandum titled “Policy Toward Chile” summarizing the guidelines from the NSC meeting. “The President has decided that (1) the public posture of the United States will be correct but cool, to avoid giving the Allende government a basis on which to rally domestic and international support for the consolidation of the regime; but that (2) the United States will seek to maximize pressures on the Allende government to prevent its consolidation and limit its ability to implement policies contrary to U.S. and hemispheric interests.” The directive authorized U.S. officials to collaborate with other governments in the region, notably Brazil and Argentina, to coordinate efforts against Allende; to quietly block multilateral bank loans to Chile and terminate U.S. export credits and loans; enlist U.S. corporations to leave Chile; and manipulate the international market value of Chile’s main export, copper, to further hurt the Chilean economy. The CIA was authorized to prepare related action plans for future implementation. The directive contained no mention of any effort to preserve Chile’s democratic institutions or to work toward Allende’s electoral defeat in 1976.

That same day, Kissinger called Nixon on the phone and they discussed Chile. Nixon had read Allende’s inaugural speech, as reported in the New York Times. “Helms has to get to these people,” Nixon told Kissinger, referring to covert operations in Chile. “We have made that clear,” Kissinger replied.

According to the declassified telephone transcript of their call, Nixon and his national security advisor then discussed their rationale for intervening against Allende. “I feel strongly this line is important regarding its effect on the people of the world,” Nixon stated, echoing the argument Kissinger had presented to him only four days earlier about Allende’s “model effect.” “If [Allende] can prove he can set up a Marxist anti-American policy, others will do the same thing.” Kissinger fully agreed. “It will have ______ effect even in Europe. Not only Latin America.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.