From Japan Focus

Abstract: As long as U.S. military bases have existed in Okinawa, sex workers have served the troops. What has varied over the decades has been the women’s backgrounds, their working conditions, and their degree of agency. During the Pacific War, the Japanese military notoriously set up a “comfort women” system in which they enslaved thousands of women from Japan’s colonies and occupied territories to supply sex to Japanese soldiers. After the war, during the U.S. military occupation of Okinawa from 1945 until 1972, prostitution was legal, and thousands of Okinawan women were pushed into sex work around the U.S. bases in order to provide for themselves and their families. After the reversion of Okinawa to Japan, Filipina migrants replaced Okinawan women in the entertainment districts around the U.S. military bases. A common belief has been that these women were trafficking victims. But the story of Daisy, excerpted from Night in the American Village: Women in the Shadow of the U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa, illustrates how the migrants also had agency.

Introduction

To research my book, Night in the American Village: Women in the Shadow of the U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa, I lived in Okinawa for a summer in 2003, a year from 2008 to 2009, and a few months in 2017. I wanted to tell the stories of local women whose lives were somehow entwined with the heavy U.S. military presence there—not only in the present, but also over the course of the long history of the U.S. military in Okinawa. After World War II, the U.S. military occupied Okinawa, building dozens of bases that remained after the islands returned to Japan in 1972. Today, Okinawa hosts about half of the 54,000 American troops stationed in the country.

I wanted to include marginalized voices, like those of women who migrate to Okinawa and its base towns for employment. While in Okinawa, I heard rumors about Filipina women who had been trafficked to the island to work in the entertainment areas around the bases. I had worked with counter-human-trafficking organizations in Cambodia and knew the classic story: traffickers lure a woman from her home with false promises of a good job, perhaps in a hotel or factory, and then force her into sex work. This is what I imagined happening in Okinawa.

But when I sat down with a Filipina woman who had worked in Okinawa’s base-town bars, her story surprised me. During my interview with Daisy in 2017, she repeatedly emphasized her agency. She said she had chosen to migrate to Okinawa, knowing the risks; she had chosen whether or not to engage in sex work; she had taken a difficult situation and used it to her advantage. The ending of her story was not like I had imagined: it was happy. Academic works I read detailed the many vulnerabilities and structural constraints of work like Daisy’s, but some also emphasized the migrants’ agency (see Rhacel Salazar Parreñas’ Illicit Flirtations: Labor, Migration, and Sex Trafficking in Tokyo and Sealing Cheng’s On the Move for Love: Migrant Entertainers and the U.S. Military in South Korea).

However much agency women like Daisy had, in 2004 the U.S. State Department categorized the Filipina migrants in Japan as trafficking victims. Embarrassed, Japanese lawmakers curbed the number of Filipinas who could enter the country on entertainer visas. As a result, there is no longer a vast population of Filipinas working around the U.S. military bases in Okinawa today. Many of those who remain migrated illegally or through marriage. These marriages are sometimes business arrangements set up by a broker or friend. Situations like these can make the migrants more vulnerable to abuse than the legal entertainer visa system of the past.

Writing about the U.S. military bases in Okinawa and the communities around them meant constantly challenging my expectations. The more time I spent on the island and the more people I interviewed, the more I saw complexity. While the majority of Okinawans don’t want another base on their island, and there is a long history of resistance against the U.S. military presence, many locals choose to interact with the bases in some way. This seems especially true for women, who may date or marry U.S. servicemen or work in the base entertainment areas. Contradictions are at the heart of the story. A woman might have a U.S. soldier husband but secretly want a base reduction. A woman might have borne the work of boosting militarized masculinity, but say she was the one who, in the end, got what she wanted.

Daisy

Daisy wanted a better life for herself and her mom—for her mom, especially. When Daisy was young, her family lived in a rural area of the Philippines, a “simple life” where candles lit the night and banana leaves served as umbrellas. Daisy remembers enjoying herself, unaware of any other way to live. But she also watched her mom work herself ragged, raising seven kids on her own. To put food in their mouths, Daisy’s mother managed orchards of banana, coconut, and cacao trees, hauling produce to market twice a week. She’d come home late at night, drunk. She’d wake at four in the morning for another day of work, sometimes still drunk. If Daisy didn’t hear her stir, she would check that her mother was breathing. She prayed to God for her mom’s life.

There had been too many tragedies. When Daisy was a toddler her father died from colon and liver cancer. A couple of months later, her baby brother died in a fire. Daisy doesn’t know how it happened. Her mother was at work, leaving the kids home alone. Daisy remembers fire licking across their roof, but the house didn’t burn down. The flames took only her brother. After that, her mother never left them alone again.

Daisy was the second-youngest child but took on the responsibility of caring for her mother and younger sister when the family left the southern island of Mindanao to escape guerilla fighting. Her oldest sister had her own problems: ten kids and a husband who beat her. Her older brothers had left for work on Luzon. So, at age sixteen Daisy dropped out of high school and started working to support her mother and sister. First, she served as a live-in maid for a wealthier family, making two hundred pesos, or about five dollars, a month. Whenever she could, she snuck in time to read English-language magazines, studying on her own what she couldn’t in school. After that, she worked a stint as a nanny, cut short because the boss was “not good.” The next job that she found, at a bakery, paid double the one as a maid. The owner, a pharmacy student, was kind and loaded Daisy with bread, cheese, and candy when she went home to visit her family. Then, Daisy moved on to a printing factory in Manila, where she silkscreened T-shirts. That paid the best of all, thirty-five pesos a day with room and board. Daisy had brought herself a long way—but still it wasn’t enough.

As a kid, Daisy had visited her cousin, whose father was an American soldier. Daisy’s aunt had met him during World War II. Looking around their house, Daisy thought, “Oh my God—they’re millionaires. One day I want to have this.” She started clipping pictures of houses from magazines and promised her mom that one day she would build her a house like that.

To fulfill her promise, she needed to earn more money. So, when Daisy was twenty-one, she decided to go to Japan. She knew what she was risking. She had heard stories about other girls who had gone on entertainer visas, stories about girls murdered around the U.S. Navy base in Yokosuka. She knew what everyone thought when you said you were going to work in Japan: you were going to sell your body. Daisy had never even been on a date, avoiding men because she feared they would derail her dreams. Her mom begged her not to go, to stay at her job in Manila. But Daisy was determined. She could earn far more in Japan than in the Philippines. She told her mom she was unafraid, even of death: “If it’s your time, it’s your time.” With her oldest niece, she applied for and got a six-month entertainer visa to work in Japan. Officially, the visa was for cultural dancing, but Daisy didn’t know what awaited her across the sea.

The promotion agency decided where each girl would go within the country. Daisy’s niece, who was tall and beautiful, got sent to mainland Japan. “They said mainland Japan is first-class,” Daisy told me, laughing. “I’m probably not that pretty.” Daisy was assigned to Okinawa.

Before leaving, she asked God for an angel to guide her. “Please don’t let me sell my body,” she prayed.

As long as U.S. bases have existed in Okinawa, so too have sex workers to serve the troops. For both the Imperial Japanese Army and the U.S. military, sex work has been seen as a natural and necessary complement to soldiers in order to keep them in fighting shape. What has varied over the decades has been the women’s backgrounds, their working conditions, and their degree of agency. During the Pacific War, the Japanese military notoriously set up a “comfort women” system in which they enslaved thousands of women from Japan’s colonies and occupied territories to supply sex to Japanese soldiers. These Korean, Taiwanese, Filipina, and other Asian and Pacific Islander women endured systematic rape and abuse wherever the Japanese military went, and Okinawa was no exception. Before the battle, the Japanese military forcibly brought thousands of Korean women to the southern islands and established some 130 “comfort stations” across the prefecture. The kidnapped Korean women and a small number of Okinawan women were made to serve dozens of men a day. Most of the women died during the battle. Some who survived continued working, now servicing American soldiers.

Following Japan’s surrender, Japanese authorities rushed to establish new “comfort facilities”—these for the American occupiers. They reasoned the men would need sex, and without such a system they would take what they wanted from the public. In Tokyo, the Japanese government and police forces worked with brothel owners, doling out direction and government funds. “A hundred million yen is cheap for protecting chastity,” a Ministry of Finance official said. Impoverished women were recruited to work for the good of the nation, a sacrifice to protect more affluent women from harm. “To New Japanese Women,” a sign in Tokyo’s Ginza district announced. “As part of urgent national facilities to deal with the postwar, we are seeking the active cooperation of new Japanese women to participate in the great task of comforting the occupation force.” Soon there were “recreation and amusement” centers across mainland Japan, segregated by the race and rank of customers, where a dollar bought a GI sex. Servicemen poured into the centers, until after only a few months the U.S. occupying government shut them down, trying to stanch the explosion of venereal disease. Officials continued to permit prostitution, however, now confining it to certain city districts. In the postwar devastation, tens of thousands of Japanese women supported themselves and their families with this work.

Under the separate U.S. administration of Okinawa, the story was similar but different. Both the U.S. military and Okinawan leaders condoned prostitution, and thousands of Okinawan women were pushed into sex work to survive. With the loss of male providers in the battle and the loss of farmland in the building of bases, they didn’t have other options. A key difference was that in Okinawa the drawn-out occupation meant state-sanctioned prostitution lasted longer.

In his firsthand account of occupied Okinawa (Okinawa: A Tiger By the Tail, published in 1968), veteran M.D. Morris writes that “for the common good” U.S. military officials organized a prostitution district after the war, and before they made it legal: “some wiser, saner heads worked out an off-the-record arrangement whereby all interested girls were assembled in a single area in which drinking, money, medical examinations, and an orderly movement of actually thousands all were controlled closely.” Military buses took troops to this area after-hours, until “some chaplains and others” banned the buses from stopping there. Instead, the buses “slowed down to a low-gear crawl,” and men jumped on and off the moving vehicles. When the “crusaders” finally got their way and shut down the prostitution district, the sex workers scattered. The U.S. military became unable to enforce medical examinations, and “the island-wide venereal disease rate skyrocketed.” Fees for sex also increased, and troops resorted to stealing cars to reach brothels. Or, bored again, they became generally drunk, disorderly, and dangerous. “Once again innocent Okinawan girls, instead of their more willing sisters, fell victims to the inevitable violent prurience,” Morris writes. Just as for Japanese authorities, for Morris and others in the U.S. military community on Okinawa, there was a dichotomy between “innocent” local women and “their more willing sisters.” In their minds, depending on the regulations surrounding sex work, one group of women or the other was going to field the American soldiers’ “inevitable” and “violent” lust.

With the unofficial prostitution district shut down, Okinawan women started renting rooms in residential areas to see customers. In one town, now a part of Okinawa City, local leaders rallied to kick out these women so American soldiers wouldn’t be prowling their streets looking for sex. The locals brought their grievances to Major General Alvan Kincaid of Kadena Air Base, but he brushed them off, saying, “They’re just healthy, red-blooded young GIs, so there’s nothing we can do. Soldiers’ sexual affairs are none of our business.” Later—after the conflict between local residents and U.S. soldiers escalated, with GIs threatening to torch the mayor’s house if he intervened—Kincaid decided it was his business. He presented the local leaders with a solution: build a “special district” on the edge of town.

In this way, Okinawan officials began collaborating with the U.S. military in building prostitution districts around the bases. The public debated whether these “dancehall[s] and facilities for recreational sex” would be a boon to local society—bringing in money, limiting the spread of venereal disease, and protecting “innocent” women and girls—or whether they were immoral and harmful to the women who worked there. Female activists protested the districts, citing the latter, but didn’t succeed in stopping them.

In these new entertainment areas, the U.S. military instituted an “A-sign” system in an attempt to control sexually transmitted diseases. Beginning in 1953, GIs could only frequent establishments officially “approved” by the U.S. military and displaying a big red A. Bars, restaurants, and clubs got this stamp of approval when they passed sanitary inspections and subjected their employees to medical testing. Still, STDs remained a problem. In 1957, one marine corps division reported that a quarter of its troops had been incapacitated by venereal disease. The next year, the number was more than a third. In 1964, the Washington Post reported the VD rate among all marines on-island was “so high” it had “been ‘classified’ by the command.”

M.D. Morris describes one of these areas as “a neon-lit nirvana for Neanderthals” patrolled by military police and “teem[ing] with enlisted service personnel of all branches, colors, and sizes.” Pawnshops offered quick cash to GIs looking to pay a bar worker’s “out fee.” The two could “then retire to one of the ‘hotels’ in the area, after which he [would] sweat out the next two weeks hoping he [hadn’t] gotten VD.” In the Saturday Evening Post, establishments selling sex were “joy palaces”—“more than 1000” with names like the “Venus, the Butterfly, the Cinderella and the Chatterbox . . . each advertising with gaudy neon the presence of ‘many-beautiful-hostesses!’” The 1957 article reported Okinawan women were “delighted” by their new profession because they had a tradition of selling their bodies to soldiers: “Okinawans were used to Japanese troops before the war and accepted marriages of convenience. They are now delighted by what Americans are willing to pay for company and entertainment.”

Needless to say, not all the women were delighted. Suzuyo Takazato explained the debt-bondage system that kept women indentured to brothels during the occupation. In a typical example, the daughter of a poor family agreed to (or was coerced into) sex work, and in return the brothel gave her family a sizeable loan. This allowed the family to eat, but the woman became indebted to the brothel, carrying a high-interest loan that was nearly impossible to pay off, no matter how many U.S. soldiers she serviced a night. Takazato said the fee for sex in those days was five dollars a person. A whole night, one veteran told me, cost twenty. These earnings could be cancelled out by the penalty fees the brothel imposed: Twenty dollars for missing work on a U.S. military payday. Ten dollars for missing work because of illness or menstruation. Other high fees were for room and board and personal products. The fees added up, along with the loan’s high interest rates, so when a woman got paid at the end of each month, often her debt had increased. According to Takazato, the average loan a sex worker carried was $2,000. “Too much,” she said, “because in those days, a teacher’s salary was $100 a month.” The highest loan reported was $17,000.

Some Okinawan women were able to operate outside the debt system. “Honey” was a postwar term for a woman who secured a longer-term relationship with an American soldier, who might put her up in an apartment and buy her nice things. Okinawans adopted the English word after noticing the GIs’ nickname for women. Among locals, honeys were disdained for their perceived immorality, while also envied for their material advantages. One Okinawan woman remembered honeys who enjoyed “gifts of chocolate, soaps, and face creams” and donned new clothes, while everyone else wore “coarse and drab” things, “torn at the seams and worn in the seats.”

In this postwar landscape—with so many women in sex work, and prostitution sanctioned by the U.S. military, and a great economic disparity between U.S. soldiers and locals—the purchase of sex became commonplace for GIs. Marine Corps veteran Douglas Lummis said that when he arrived on Okinawa in 1960 the base commander told his men, “On Okinawa the number of prostitutes is approximately the same as the number of U.S. military [soldiers]. There’s just about one for each of you.” Lummis recalled that hiring a prostitute became “just something that one could do. And virtually everybody—with some exceptions—virtually everybody availed themselves of that service. And that’s part of what made Okinawa exotic in the Marine Corps imagination.”

The number of sex workers in Okinawa peaked during the Vietnam War. A 1967 police survey determined some 7,400 women were working as prostitutes. Another source estimated the number was double that—which meant about one in every twenty to twenty-five women between the ages of ten and sixty was involved in sex work. Together, their labor generated more money than any other local industry— more than pineapple and sugarcane farming combined. One Kin club owner recalled how much money GIs spent during the Vietnam War at his establishment, which employed twenty “hostesses.” The cash was literally overflowing: “We stuffed [the bills] into buckets, but they still overflowed, so we had to stomp the piles down with our feet. . . . Dollars were raining on us.”

Suzuyo Takazato told me that in 1970 the Ryukyuan government had the opportunity to enact Japan’s Prostitution Prevention Law, which had prohibited sex work on the mainland since 1958, but decided to wait two more years, until the official reversion. “Here is the twisted feeling of Okinawan people,” she said. Lawmakers knew the dire situation of many indentured sex workers, but were afraid that if they banned prostitution, U.S. soldiers would commit rape. They also wanted to keep that money in the economy. “In a way,” Takazato said, at that time Okinawa was “economically supported by individual women who worked as prostitutes.” These women were the ones who pulled their families— and all of Okinawan society, really—out of postwar poverty. But in society’s eyes their hard work and sacrifices weren’t selfless or noble or admirable; they were shameful.

When Okinawa reverted to Japanese control in 1972, prostitution became illegal and women were freed from their debt bondage. Some continued to work, with local police often looking the other way. Those who wanted to leave the profession received financial assistance and access to temporary living facilities, thanks to the Japanese government. Takazato said the government also helped some brothel owners become hotel owners. But in a way Tokyo also authorized the next wave of sex workers by issuing entertainer visas to overseas workers. Soon, Filipinas replaced Okinawans in the red-light districts outside the base gates.

Stepping off the plane in Okinawa, Daisy was careful to touch her right foot to the ground before her left. That way, she would head in the right direction. It was March 1992, and she was twenty-four years old. Her first impression of the foreign island where she would live and work the next six months was that it was clean. After the chaos of Manila, a megacity, Okinawa seemed small and quiet and so very clean.

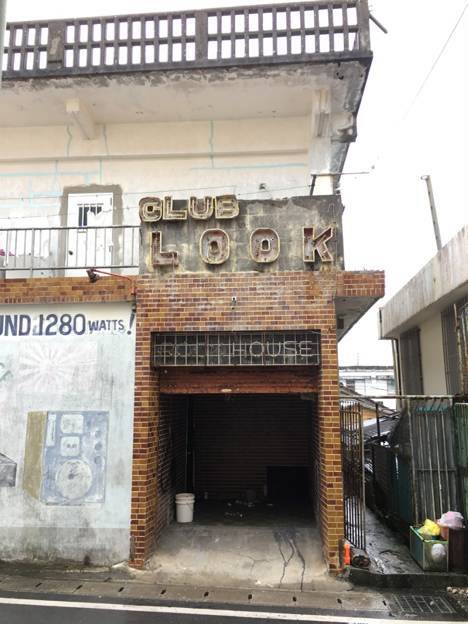

She moved into a house in Kin outside Camp Hansen, where she would live with the other Filipinas working at the club. In those days, Kin was crowded with clubs and women from the Philippines. The place Daisy was sent to was run by an Okinawan woman, the mama-san, who owned three bars in one building, two downstairs and one upstairs. Daisy learned she would rotate among them, talking with customers and dancing on stage. The pay was impressive. Even just her new food allowance—10,000 yen a month, plus rice—was more than she had made at the printing factory.

Women like Daisy replaced Okinawans in the entertainment districts around U.S. military bases because of economics. When Okinawa reverted to Japan in 1972, the dollar gave way to the yen as the islands’ currency. The new exchange rate raised prices on American servicemen. Meanwhile, as part of Japan and no longer a de facto colony, Okinawa came to enjoy an economic boost, with women’s economic power increasing, too. Presented with better opportunities for education and employment, many no longer had to turn to sex work. Eventually, the primary way local women and American servicemen interacted was through dating—mixing in the island’s clubs and shopping centers.

Meanwhile, in the Philippines, the problems of excess labor and foreign debt caused the government, as part of its economic strategy, to encourage women to migrate overseas as domestic help and entertainers. Throughout the 1980s, the number of Filipino contract workers migrating to Japan rose steadily; in 1981 there were 11,656; in 1987 there were 33,791. The vast majority were female entertainers. On the mainland, many went to work in hostess clubs serving Japanese customers. In Okinawa, they were concentrated around the bases. Though the Philippines had its own U.S. military bases, women could make more money in base-town entertainment areas in Japan.

By the mid-1980s, an estimated four thousand Filipinas worked in the bar areas outside U.S. military bases in Okinawa. Okinawan women who stayed in the business moved to areas that served mostly Okinawan and Japanese men—at higher prices. According to Suzuyo Takazato, Japanese tourists paid $50 for sex, while outside the bases what had cost Americans $5 during the occupation now cost $20. Women from other countries including Thailand also migrated to work in Okinawan bars and clubs, but the vast majority were Filipina because the governments of Japan and the Philippines made it easy for them to migrate. While legal, the entertainer visa system was largely yakuza-controlled, including the promotion agencies in the Philippines. A bar owner in Okinawa paid a yakuza-run promotion agency a fee, and the agency recruited women for the bar and paid their salaries, taking big cuts for themselves. “My salary is $400 a month, but I only receive $290 because $10 is deducted for insurance and $100 for the manager in the Philippines, at the promotion agency,” explained one Filipina working in Kin in 1989. The women’s travel to and from Okinawa was also deducted.

The women were legally in Japan as “overseas performing artists,” meant to sing or perform cultural dances in groups. So, some were shocked when, on their first night, they learned they’d have to dance alone, wearing little to no clothes. One woman, Rowena, cried her first time onstage, while her “papa-san” shouted, “Take off your bra.” He said if she lost her panties, too, she would be “number one.” Along with performing, women were required to sell a certain “quota” of drinks per month. At one Kin club in the late 1980s, the quota was four hundred. Each drink cost an inflated $10, and the woman received a $1 commission. The penalty for failing to make quota was receiving just half the commission. Doing this work, most women received only a couple of days off per month.

Life in the clubs was about luck—or, as Daisy saw it, providence. Women had no control over which club the promotion agency sent them to, and clubs differed according to owner. Some had high drink quotas and would send women back to the Philippines if they didn’t meet them. Others forced women to dance naked and perform sexual acts on customers in “dark corners.” Some places controlled the women’s movements outside the club, going so far as to lock them inside their rooms. In 1983, a fire raged through one Kin establishment, and two Filipinas died because they were trapped behind bars.

Before Daisy’s first night of work, she repeated her prayer: “God, please, please send an angel to guide me.”

The rest of Daisy’s story is described in Night in the American Village: Women in Shadow of the U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.